"Very Resistant" Monterrey Oak Nine months into symptomology (October 2019 left)

The same tree 10 months later (August 2020 right).

This video presentation provides an overview of the subject matter of this webpage.

Table of Contents

“Susceptible” / “Resistant” Quandary

A. Merriam Webster

-

Susceptible: open, subject, or unresistant to some stimulus, influence or agency

-

Resistant: giving, capable of, or exhibiting resistance; i.e. the inherent ability of an organism to resist harmful influences (such as disease,…etc.)

with immediate flash mortality

B. Northern State Experts

-

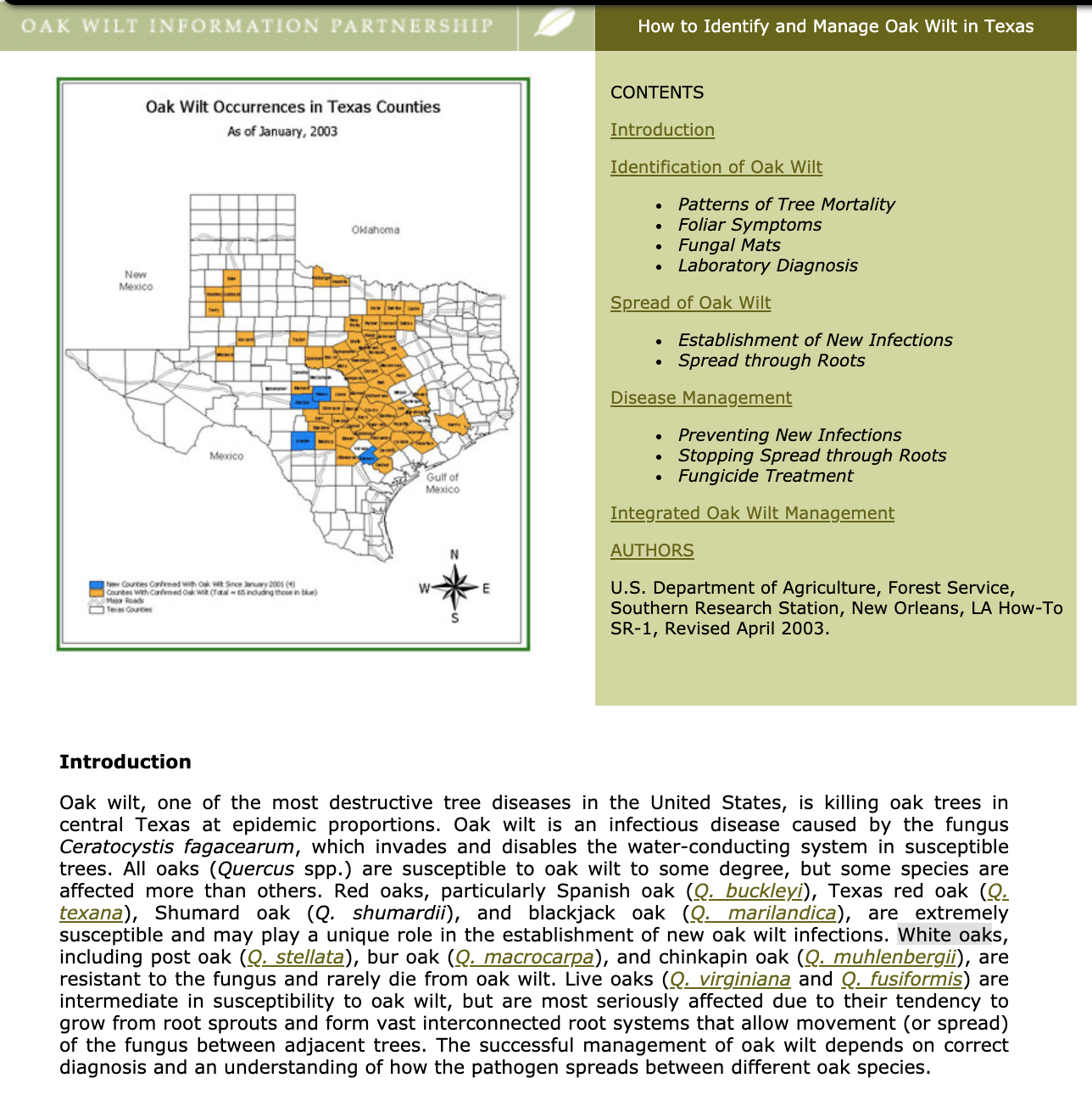

General consensus is that “all oaks are susceptible” to oak wilt. By the statements made below by various state experts, it would appear that by "susceptible" these experts recognize that all oaks species are capable of becoming infected and that affected to the point of mortality is a likely consequence. The position that most susceptible oak species will eventually succumb significantly or completely to the disease is a significant divergence from the Texas Forest Service (TFS) position.

-

General consensus is that white oak species are “more resistant” than Red Oak species. Here is where the significant difference between the Northern experts and the TFS perspective becomes apparent. In the Northern states the spectrum of resistance is presented as variations in duration of time and progressive decline until mortality occurs. Cases of survival and recovery are the exception not the norm. A second aspect of resistance they convey with the use of “resistant” is that the probability or likelihood of contraction by those in the white oak group is diminished due to: white oak species populations are smaller than the red oaks, inter-species grafting for various reasons is not as common, and that intra-species grafting is also not always a given.

Mortality durations (if untreated):

Red Oak = less than 1 year;

European white oaks = less than 1 year;

Bur or Chinkapin Oak: 1-5 years;

White Oak: 4-8 years.

A very interesting insight by one northern expert, is that he suggested not to use the term “resistant” on account of the connotation it can convey - namely, that the public may infer that “resistant” trees can avoid contraction of the disease or if they do – they rarely die and only lose a limb or two. Instead he prefers the use of the term “tolerance,” which has a more accurate connotation of assumed infection of and impact by the disease, which it can for a time successfully tolerate for brief or in some instances a longer duration of time.

National View

“Other white oak species (e.g., Q. macrocarpa, Q. fusiformis, Q. virginiana) may exhibit moderate resistance, with tree mortality occurring several years following infection.”

National Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) View

“Post oak may be the most resistant while Lacey oak and bur oak are the least.”

“Post oak tends to be the most resistant of the group while bur oak is the most sensitive…Whereas in the red oak group the disease may kill the tree in a few weeks, in the white oak group it may take several years. However in bur oak, symptoms are essentially the same as in the red oaks, and the tree may die within one growing season.”

Great Plains View

Once infected…many white oak species die from oak wilt. Although an infected, highly resistant white oak may not die from oak wilt, the death of major limbs may render the tree undesirable as a landscape or specimen tree.”

Kansas

“The white oak group is more resistant to the oak wilt fungus: Bur, Chinquapin, Post and White oaks, may survive several years of infection.”

Iowa/Missouri

“Trees in the white oak group typically develop symptoms more slowly [than red oaks]. For example, Bur Oaks typically die after 1-7 years, showing progressive dieback during the process. White oaks may take up to 20 years to die, and some white oaks survive the disease.”

Kentucky

“White oak species, on the other hand, are more resistant and may live for several years after infection.”

Wisconsin

“Oaks in the white oak group (white, swamp white, bur, and others with rounded edges) are less susceptible. Infected trees in this group will drop their leaves on one or more branches for several years in a row. In other words, trees in the white oak group take longer to die and show more chronic symptoms.”

Michigan

“White Oaks may also recover from OW [oak wilt] infection – there are exceptions.”

Minnesota

“Bur oaks die between one and seven years after infection, while white oaks die from one to over 20 years after infection.”

Indiana

“The white oak group contains species that are much more resistant to oak wilt, so oak wilt symptoms appear more gradually. Oaks in this group may have a single limb or scattered limbs with disease symptoms, and the disease will progress down the tree only a short distance in one growing season.

Premature leaf drop is generally not pronounced and an infected tree may survive several years before it dies. However, infection will result in dead limbs throughout the crown of the tree and will become more noticeable each year as the infection spreads. It is easy to mistake the gradual dieback for other oak problems.”

Ohio

"Oaks in the white group (Bur, Chinquapin, Post, Swamp White, and White Oak) are more tolerant of the disease and may survive infection for one or more years while displaying decline symptoms."

Pennsylvania

“Oak wilt moves much slower in members of the white oak group, usually killing a branch or two a year, and it can take years for infected white oak group trees to succumb.”

New York

“White oaks can take years to die…”

Illinois

“The [white oaks] may die in one year, but usually die slowly over a period of several years or more. After two or more years of progressive die-back, infected white oaks have sparse crowns and eventually die from oak wilt or secondary causes. Bur oaks are intermediate in susceptibility and may be killed as quickly as red and black oaks or as slowly as [the white oak].”

C. Texas Forest Service

***NOV./DEC. 2019 UPDATE REVIEW***

After an aggressive solo campaign that consisted of: building my website treatise on oak wilt, numerous emails and phone calls – both with peers, AgriLife agents, online journalists, and Texas Forest Service personnel, coincidentally, about a month later - various adjustments to the epidemiology of white oaks species and oak wilt occurred in various places within https://texasoakwilt.org/faq.

The two main positive aspects of the update are that they moved the tolerance level of the white oaks a significant bit closer to where it should be for at least some of the species, and as a second component of that – they acknowledge these same white oak species are akin to Live Oaks in regards to interconnected root systems and lastly, (albeit very briefly) they temporarily opted to use the more scientifically accurate terminology in their presentation of the information on both sites.

On https://texasoakwilt.tfs.tamu.edu/ - they briefly used the tolerance terminology exclusively on the Introduction page, but unfortunately and unexplainably reverted back the very next month to the synonymous utility of susceptible/resistant that you can find critiqued along with an argument for the uniform use of tolerant/tolerance terminology in the “Author's Response” below (this link: https://web.archive.org/web/20191225141655/https://texasoakwilt.org/oakwilt/ caught them in midst of the change – the white oak section clearly rough draft form with both terms present). I was encouraged though to see that their main website that they updated (Dec. 2019) also exclusively utilized the “tolerant” terminology until another unfortunate reversion back to resistant” terminology (mid-January 2020).

***Note: Regardless of the repetitive changes of the terminology utilized – I will consistently opt to employ the superior “tolerance/tolerant” terminology in my critique.***

I am not per se claiming credit for the impetus of the change, but merely conveying the historical update context.

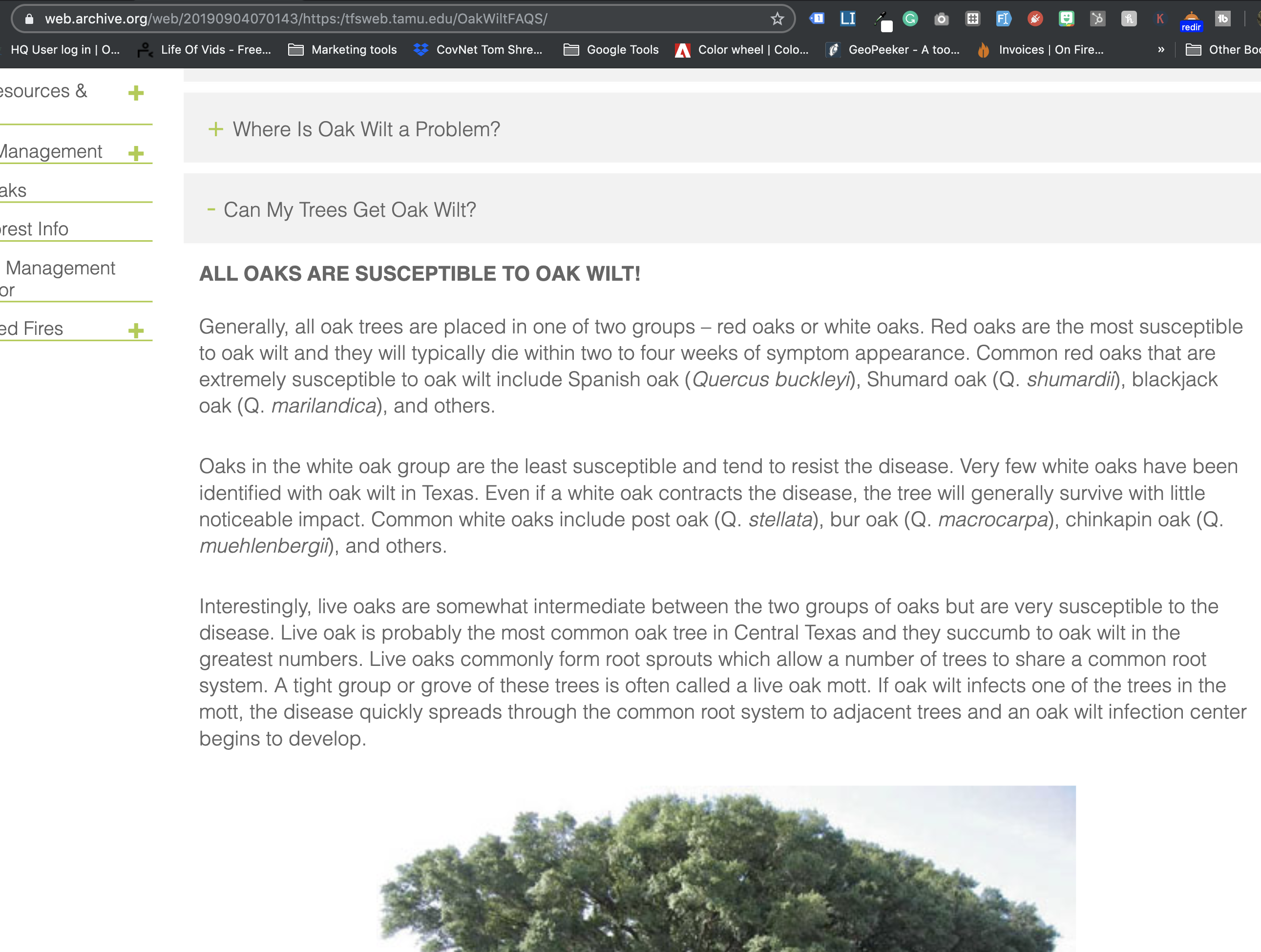

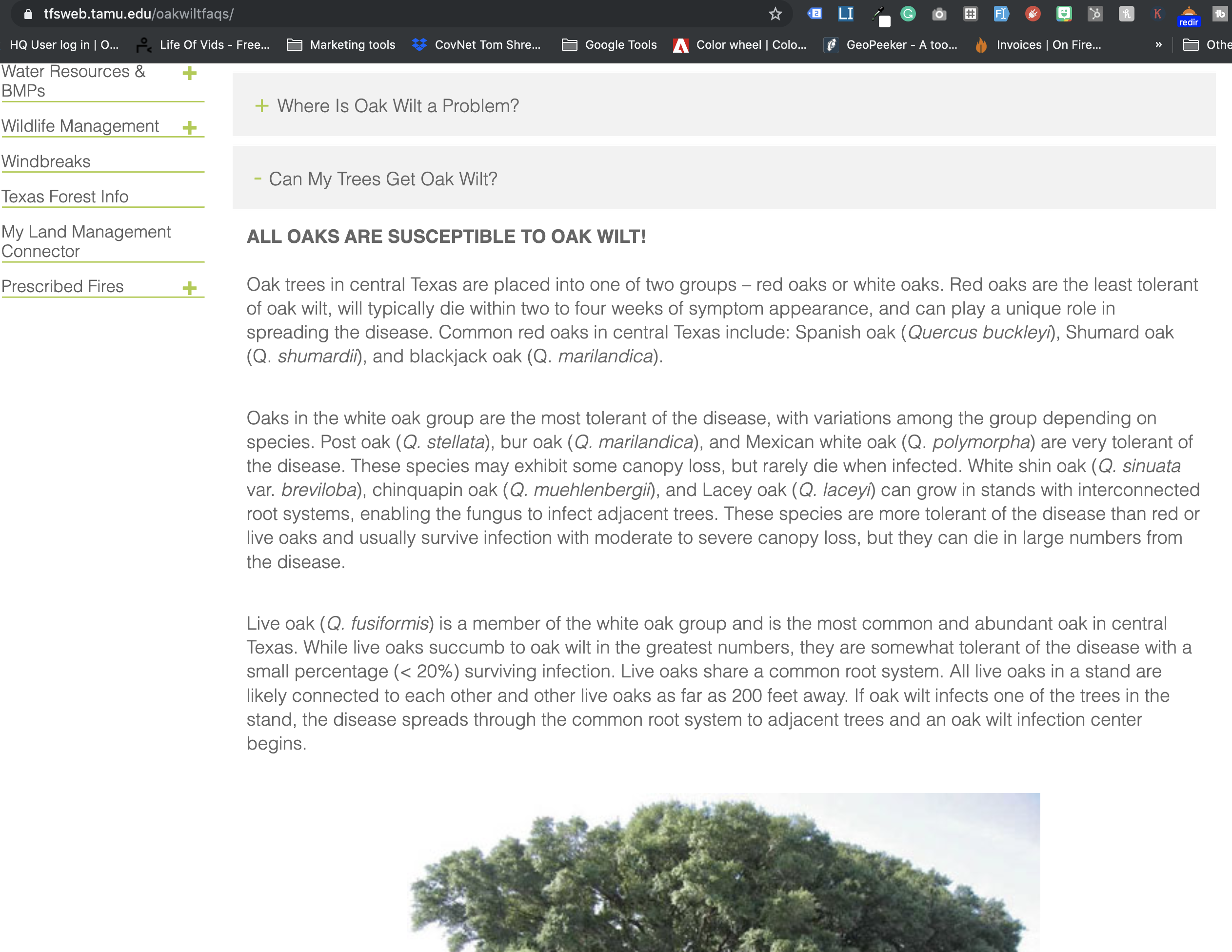

Let’s look at the most obvious shift in the TFS position on white oak tolerance (see image above of pre-update and update side by side). What is without a doubt 100% crystal clear is there was a full-scale abandonment and deletion of the 16+ year-long position wherein they claimed all - “white oaks rarely die from oak wilt.” This move to completely abandon that untenable position, which has remained unaltered on www.texasoakwilt.tfs.tamu.edu from Fall 2003 until November of 2019, is a great move forward, but it does raise questions.

So now we can be sure that some or most of the white oaks don’t rarely die, but many questions arise, such as: How often do they die? How tolerant is each species? Upon what basis is that tolerance substantiated? What is clear is that they are not yet saying most will die nor are they saying it would appear that even most will experience significant canopy loss, both of which is the general experience of Northern experts as well as my experience with white oak species (only exception – the Post Oak) in Texas.

What the TFS does say is that only “some” canopy loss will be exhibited. One wonders is “some” defined as 49% canopy loss – or maybe even more? If so, I’d venture to presume most consumers would respond that, that amount of canopy loss would be better described as “unacceptable” rather than “some” – at least enough for most consumers to likely opt to remove and replant (see “Great Plains View” above).

Next, looking at the adjustment to the Lacey, White Shin (Q. sinuata var. breviloba), and Chinkapin, we see that the TFS allows that these particular species "sometimes" have interconnected root systems like Live Oaks and when they do that it may cause “higher infection and mortality rates than other white oak species.”

Let’s break this down. Why “sometimes” interconnected roots? Those of us who spend considerable time around these three species in their native habitat know that they are frequently found in mott groupings. Further, why not the inclusion of the Durand Oak (Q. sinuata), which is obviously very closely related to the Shin Oak? While we are at it – why not throw in the Monterrey Oak which is known to cross-pollinate and be the most likely to in general “morph” with every oak in the area. Similar to Live Oaks –it is in the DNA of these native central Texas white oaks to grow in motts and or readily graft (There are many videos on my YouTube page that display this fact quite succinctly).

In regards to higher mortality rates – what does it matter if it is one infected Lacey Oak or 100 Lacey Oaks?! If the tolerance level of Lacey Oaks is low and full mortality is say 80% in a year to three years – like the Live Oak, then is it not just a question of mathematics to project from a singular tree to the 100 trees? If not, I’d like to understand what exactly the TFS is thinking along with a thorough exposition for that basis.

On their FAQS page (also applicable to the same incoherent claim made on the main website – see below) they say that these three white oaks “usually survive” but also “die in large numbers.” This is clearly a contradictory position. At a minimum “usually” means at least "more often than not". At a bare minimum then we are talking about at least 51%+. Regarding “die in large numbers” – what constitutes large? Wouldn’t say small numbers be less than medium, medium numbers be say 49-51%, and large have to be over 51%+?!

Obviously that math doesn’t add up.

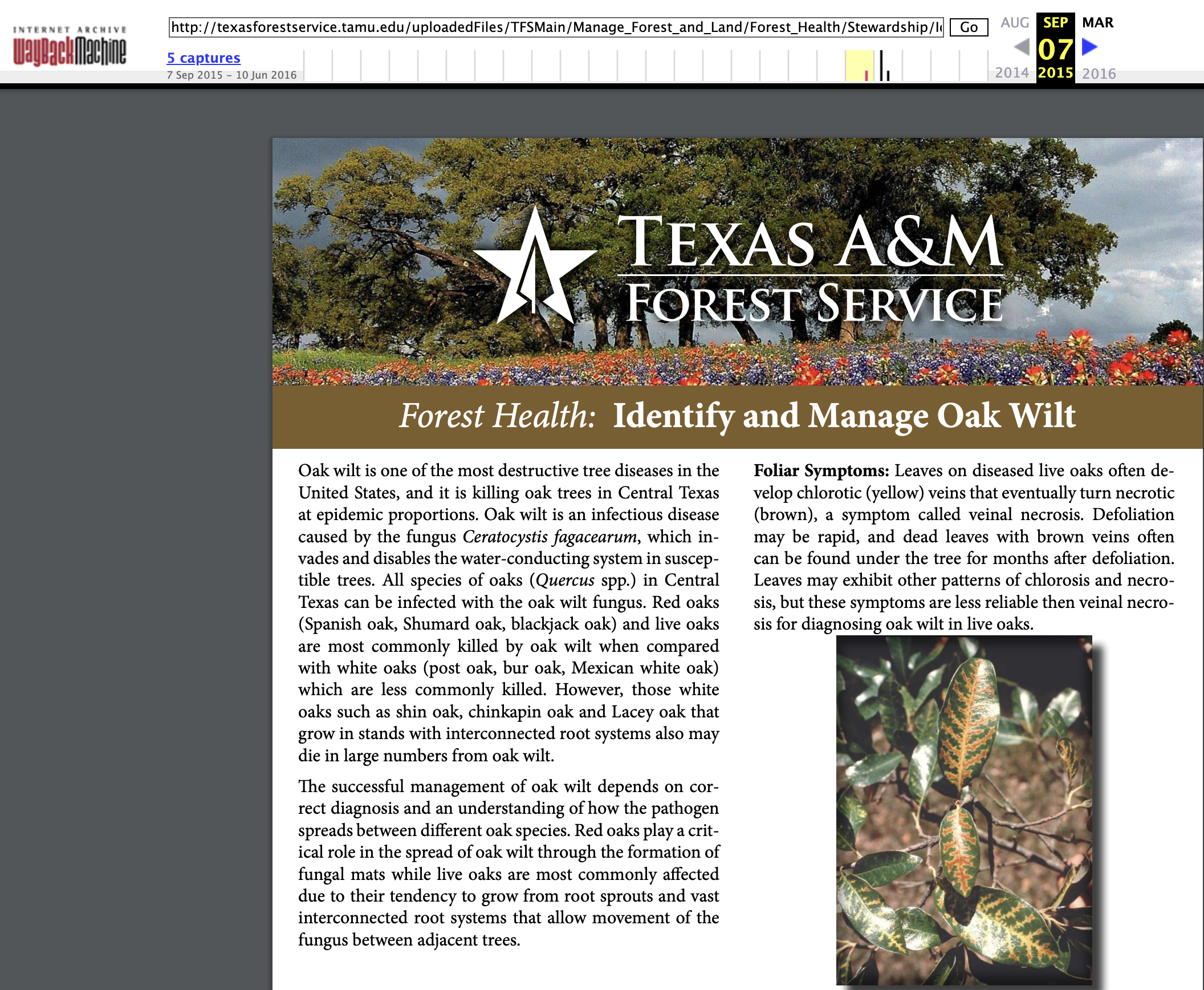

Why is the seminal TFS oak wilt update (found only on their main website as early as Sept. 2015) I’ve quoted and provided a link to below not yet uploaded to https://texasoakwilt.tfs.tamu.edu/ website where one would reasonably expect it to be published? Why not just copy and paste the prior update terminology - including the wording that they “may die in large numbers from oak wilt”?

Higher mortality rates and large numbers are nowhere near saying the same thing (ex. a 2% mortality rate is higher than a 1%!). One may well wonder if this particular page has the most watered-down version of the update because it very probably of the three pages the one with the by far highest page views. Would anyone from the TFS like to show us some Google analytics on these three pages, please?

Also, why did they make another regression by updating the update and moving from “most white oaks will exhibit some canopy loss” to “many…”? Though a definite move in the right direction, this new website update is not nearly far enough to reflect consistent, repetitive field observations I, as well as other experts have made for over the last decade (at least), and it creates many new questions.

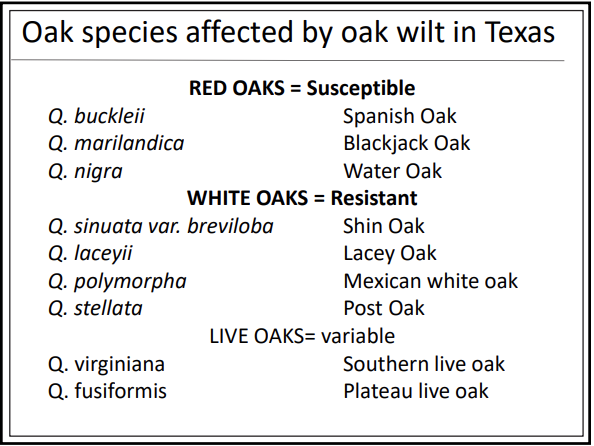

As to historical terminology usage and meanings conveyed on this site and other corresponding partner organizations and scientists - the consistent position by the Texas Forest Service is that “all oaks are susceptible to infection from the fungus.” Further, this susceptibility is tiered in the following way:

“Red oaks are extremely intolerant (Dec. 2019 worded “most susceptible”) of the fungus”, “Live Oaks are intermediate in their tolerance (now “susceptibility”)”, and “white oaks show some tolerance.”

(Each quote above reflects the November 2019 update favoring the new “tolerance/tolerant” terminology I had advocated prior to the update, which they capriciously altered back to resistant/susceptible terminology just one month later.

-

Regarding resistance, historically the Texas Forest Service has repeatedly grouped the entire white oak family in the “resistant” category (see the screenshot w/link from inception of website up until 2019 update, the TOWQ course presentation image w/link below, the prior brochures still being handed out, the joint educational activities with AgriLife, etc,). Even given the oak wilt update document as well as the Nov. 2019 update – the TFS message still falls considerably short and a divergence from the Northern states “may survive” to the TFS “may die” remains regarding white oaks. An in-depth exposition on the tolerance level of each white oak species as well as a definition of their terminology are both needed from the TFS.

Before and After. Note the changes in the second paragraph. Click each image to view the source and click on "Can My Trees Get Oak Wilt?" tab.

Here we can also see a drastic white oak epidemiological change in position from Sept. 2019 to Dec. 2019 form (the two screenshot pics utilized). Let us be frank – going from “very few white oaks have been identified with oak wilt” and saying that if they do contract oak wilt they “will generally survive with little noticeable impact” to saying that three of the six listed white oaks “can die in large numbers”, is nothing short of a mess!

Unbelievably, no explanation is offered! Really?!?

Then they confuse the reader even more by saying that these less tolerant three trees “usually survive” but at the end of the same sentence say they “can die in large numbers”!?! The exclusion of the Bur oak and Mexican White oak from the lower tolerance list is unfounded.

There is plenty of science on the Bur oak and its likelihood of mortality from oak wilt researchers (see the entire first half of this page again). As far as the Mexican white oak is concerned – field observations are what got the TFS to move the tolerance gauge on the other three less tolerant oaks in the first place and field observations are the same for the Monterrey oak as they are for the three that “die in large numbers”.

Feel free to ask the TFS for the official scientific inoculation study(s) specifically validating the Mexican White oak and the Lacy oak tolerance levels. When they get tongue-tied and have none to cite – it will be clear how likely another “update” will be occurring for the Monterrey oak and the Burr oak in the (hopefully not too distant) future.

Below we will see the white oak update that predated both of these adjustments and which provided the most leverage in my campaign to encourage the TFS to get out in front of this major error in oak wilt education, which has huge implications for the entire green industry and long-term forest health.

The quote from the TFS oak wilt update - first found on their main website Sept.7, 2015 (not on their oak wilt website where one would expect them to publish it!), clearly shows the intra-department divergence of position, and which much more conforms with the northern state's experts regarding white oak group mortality:

“Also may die in large numbers” sounds a lot like – no exactly like, an oak wilt mortality center. Oak wilt mortality center language was previously restricted to what happens with red oaks and Live Oaks but now “also” these three white oak species!

Albeit, this statement appears to be guarded and tentative – one wonders if the phenomenon of a white oak mortality center is only a theoretical possibility, or has it been observed only once, or observed numerous times, or is the fungus evolving (becoming more virulent), or has the phenomenon of Texas white oaks dying in large numbers previously gone somehow unnoticed somehow, or…?

What I especially wonder is (and very likely the reader of this page), what about the other white oaks?! We all are likely on the same page more or less on the Post Oak having more tolerance than any of the other white oak species, but with the Lacey, Shin and Chinkapin oaks all on the possible oak wilt mortality center list – that only leaves the Durand, the Burr oak, and Mexican White oak in limbo if you will.

A short, cursory read of the taxonomy and characteristics of the Shin and Durand should easily alleviate any hesitancy to pigeon-hole the Durand into the same level of tolerance as the Bigelow oak aka Limestone Durand oak. The update states that “Live oaks are most commonly killed when compared with some white oaks (Post, Bur, and Mexican White) which are less commonly killed.” After serious consideration one must conclude that this statement actually affirms that these three “some white oaks” also are commonly killed – just not as commonly as the Live oak! In no way shape or form does it say:

The Mexican White, Bur, and Post oak rarely die.

Or

The Mexican White, Bur, and Post oak are very resistant.

Again, the 2015 TFS update states:

The Mexican White, Bur, and Post oak are less commonly killed.

Though there is not much field observation on Burr oaks with wilt here in Texas as of yet – we know that Jenny Juzwik (along with Dr. David Appel), groups them in the same intermediate/moderate tolerance category as the Texas Live Oak varieties (see especially: National View, Minnesota & both NRCS Views above).

We also know that they regularly treat them up north with fungicide to preserve them from dying and also that they can produce fungal mats (fungal mat formation presumes mortality!) – a fact scientifically documented in the 1970s. It is likely that these facts informed the 2015 author(s) on the only slight reduction of tolerance compared to the other three that “die in large numbers.” As for the Mexican White oak – on what scientific basis is this white oak not included in that same list of potential white oaks with probable mortality at the singular or group level?!

Further clarification on this by the Texas Forest Service (and many other issues) is still needed.

Dr. David Appel is one of the most prolific contributors to the cadre of oak wilt research for over the last three decades. In 1994 he did a great service to the Californian community by measuring the impact of oak wilt by means of an assay of sprouts upon 11 of the most common oaks that inhabit California proper for just under 3 months of observation. What in my assessment is the most succinct concluding remark found within his study?

Given our focus here on the white oak species, I’d be amiss if I didn’t point out that 6 of the 11 California oaks tested were white oaks. There were two red oak and two “intermediate” oaks (which he proffered may well produce fungal mats).

The intermediate and red are of course quite a concern as one would typically expect, but very notably 3 of the white oaks (Q. dumosa, Q. durata, and Q. suber) had very high (higher than our Southern Live Oak and close to the rating of our Escarpment Live Oak) ratings of symptoms and dieback in less than three months! In no way shape or form could they be included in the resistant category of the Q. alba or even the Q. stellata). One wonders:

-

What would have been the results for those three species and especially for the other 3 white oaks at 6, 12, 18, 24, and 60 months?! (Note: There was definite decline from week 7 to week 11 in at least study I – study II & III were just a singular 10 week study it appears)

-

Regarding the levels of classification wherein Dr. Appel appears to be defining “resistant” – would the death of 49% of above-ground tree parts in under three months qualify as “resistant”? Would this same dieback amount be acceptable for a tree-purchasing consumer looking to plant a “resistant” tree?

-

J. Pinon et. al performed a study of sprouts (see National Oak Wilt Symposium, 1992) on European white oak species and then carried to the next level by W. L. MacDonald on 14-year-old established field-grown European white oaks (same species) – and the results were even worse in the second study! What would happen if a study of field-grown Californian oaks was conducted?!

(Follow this link to purchase the book: Shade Tree Wilt Diseases)

-

Has an official, published study of the Texas white oaks: Chinkapin Oak, Durand Oak, Lacey Oak, Mexican White Oak, and Limestone Durand Oak matching the excellent second study by Dr. MacDonald been conducted? Dr. Appel himself has admitted he knows of no such studies regarding the Mexican White oak tolerance level. Other experts have confirmed at none of the other white oak species have either. Obviously, one cannot proffer what doesn’t exist. This is quite an unfortunate fact. It is this fact that has greatly contributed to the dire need for the existence of this webpage and campaign of investigation – recording observations, dna diagnostic sampling, and the like…

-

According to the Texas AgriLife Research Extension in their Texas Superstar Selection Policy they emphatically state: “Every effort is made to ensure that highlighted plants will perform well for Texas consumers.”

How did Texas AgriLife Research determine that the Chinkapin and Lacey oak (the latter they actually went so far as to specify a 7-year intensive scientific trial period!) met the disease resistance level required for the Texas Superstar designation without appropriate testing (ex. See MacDonald et. al., above)?!

died in less than a year

D. Author’s Response: A Texas Solution to the Quandary

-

Susceptible – Any and all members of the Beech family are to be included in the ability to contract oak wilt AND die as a result of infection UNLESS DEFINITIVELY PROVEN TO THE NEGATIVE BY NUMEROUS PUBLICALLY PUBLISHED STUDIES AND PEER REVIEWS.

-

Resistant – I am of the firm conviction that this term must be abandoned – in a large-scale public retraction campaign, and replaced with the term tolerance and accessibility.

As per the glossary of the premier textbook for plant pathology:

Resistance: The ability of an organism to exclude or overcome, completely or in some degree, the effect of a pathogen or other damaging factor.

Resistant: Processing qualities that hinder the development of a given pathogen; infected a little or not at all.

PLANT PATHOLOGY. 5th Ed. Agrios, George N. Elsevier Academic Press, 2005.

-

Tolerance – The ability of the tree to withstand infection for a duration of time until full mortality likely occurs or at the least more than half of the plant parts dieback. No oaks unless proven during extensive studies to NEVER experience not only mortality, but minimal if any decline, and if minimal – only temporary, minimal decline after infection, are to be given a true tolerant designation. AT THIS TIME IN TEXAS – NO OAK SPECIES IS TRULY TOLERANT.

Post Oak: Longest duration of tolerance. Likely to die in 3-5yrs as a result of the primary pathogen – the oak wilt infection, but also often combined with other contributive stressors such as drought, and or, hypoxolon, and or phytophora, etc.

Burr Oak, Bigelow Oak, Live Oak, Lacey Oak, Durand Oak, Chinkapin Oak, Mexican White Oak: LOW(intermediate/variable) tolerance as displayed on account of death OR mortality of a majority (51%+) of above-ground tree parts within 1-3 yrs. – leaving the tree as a loss and liability in the estimation of most TRAQ and or TPAQ assessments.

Black Jack Oak, Spanish/Texas/Southern/Shumard Red Oaks, Pin Oak, Water Oak: Very Low tolerance: Rapid mortality from full canopy death within 1-3 months and trunk death in under 1 year in most cases.

4. Accessibility – This new term is an attempt to further distinguish between another muddled aspect of the previous position of the Texas Forest Service. In that all oaks are susceptible – regarding specifically the overland form of transference of infection – all trees must have some level of accessibility, and with certain givens being equal it is likely any oak is accessible as any other.

For example:

Say there is a 10” DBH Red Oak with an active fungal mat with one beetle covered in spores and about to take off in flight. Let’s also say in a perfect circle around said tree 50’ away, on a windless, spring day - there are every variety of oak species of 10” DBH size and similar canopy, all of which were wounded on the trunk at 5’ simultaneously with a 4” x 4” bole cut. What tree has the highest likelihood of infection?

Without definitive study from oak species sap aroma strength and maybe more importantly - most preferred sap flavor of any or at least of this nitidulid beetle, or which direction that particular beetle prefers to go – maybe it believes flights to the right are always the best sap-feeding direction, one must conclude that all are equally accessible.

Now, that example was theoretical, but it illustrated the point successfully. In the real world though, the quantity of a specific tree, the species of the tree, the total mass or size of that tree, the proclivity of that tree to wounds – either naturally inflicted or inflicted by humans, the proximity of those trees to one another, the size and quantity of root grafts, the weather, soil type, various abiotic and biotic influences – all these things among others can impact the accessibility of a specific tree and species to infection – be it via overland or underland spread. In conclusion, regarding underland spread, I proffer the following:

All oak species can and often do graft with one another – especially in the central Texas region. In some cases, the transmission between different species may be delayed. In very rare occurrences, with little to no logical explanation – a tree expected to be grafted may in actuality not be grafted at all or the sick tree - before the fungus is able to move far enough away from the infected tree – it dies when said tree dies before it can travel to the next tree.