The Art of War - On Oak Wilt

Kevin Belter

TOWQ-183

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- War on Oak Wilt Weapons

- Spore Producer (SP) Scouting/Roguing

- Pruning/Wound Sealing

- Fungicide

- Macro-Infusion

- Micro-Injection (Low Pressure, Passive Delivery)

- Micro-Injection (High-Pressure Delivery)

- Additional Experimental Method

- Trenching

- Roguing in the Trench

- Silvicide/Herbicide

- Tree Planting

- Recommended Improvements for Increased Efficacy of the TOWSP

Introduction

“Oak wilt management” does not quite convey the right message in my assessment. Maybe if the efforts were successful – but here in Texas, we are losing this battle – badly. I believe taking on this powerful adversary with diverse arrays of tactics and ingenuity as exemplified in the heart of the approach and message of Sun Tzu can get us to that point here. A defeatist attitude is an unacceptable position. This is NOT Mother Nature taking her natural course. What is happening is a perversion of nature which we are fully responsible for by stopping the fires which regularly renewed our state and we provided no alternative means of maintaining the geographical separation of oak motts and control of oak mott root sprout expansion. Here is where the rubber hits the road – good ideas and theories and “science” get their test when action – or lack of action occurs and we observe the results. Trenches are failing because depths are not specified as deep as needed as well as roots are re-grafting after the fact. Fungicide injections are failing due to poor application timing, technique, product, and dosing issues among others. Infected red oaks with fungal mats are still standing in easy eyesight from roads in major and small municipalities in central Texas, while our northern counterparts follow diligent processes to identify and remove SP's prior to mat formation. Despite immediate painting of pruning wounds by a diligent contractor – multiple, large long deer rub wounds, varmint chew wounding, wind breaks, etc. are occurring numerous times each month and a new oak wilt centers are starting – meanwhile good-intentioned but horribly wrong educators are promoting the mantra that “oak wilt is so easy to prevent” and as a result the good-intentioned media personnel are parroting the same. Finally, the unthinkable debacle of recommending planting of oaks with a big pretty “I am oak wilt resistant” bow then come to find out that assumptions, not science, informed this recommendation and now a lot of apologies and replanting will be in the future of those unknowing and trusting consumers. Worse yet – nothing is changing.

Many of the new ideas to achieve greater success in oak wilt management come from the northern states. For the following reasons they have achieved greater control: a pro-active SP removal process, double trenching, use of herbicide and or tree removal is standard operation procedure, as well as use of herbicide alone as a chemical barrier, and they do not have their heads in the sand pushing a message of “most infected white oaks exhibit some canopy loss”, rather they are straight-forward telling the public that white oaks can tolerate the disease longer but need treatment and will likely die if they are not treated. Macro-infusion of Alamo is still the norm for method and product and with the help of Rainbow Treecare Scientific’s efforts – training is excellent and easy to get.

War on Oak Wilt Weapons

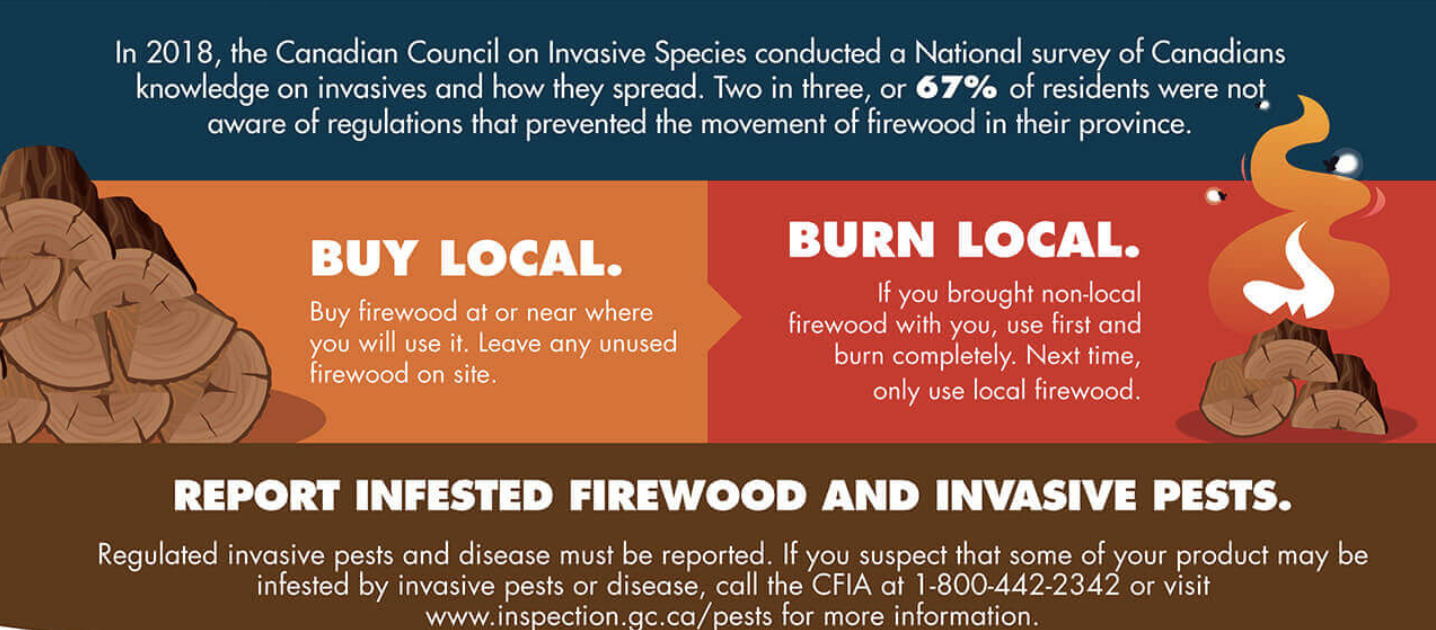

Don’t Move Red Oak or Bur Oak Wood

Though this message is fairly uncomplicated (or at least should be simple and straight-forward), I have ranked it number one to cover because at the current moment there are many yet unaffected states and there is a moral imperative for those of us with this scourge ravaging our states to protect our neighbors from the same fate as well as those yet unaffected not putting their fellows back home in danger. Some key bullet points here are as follows:

I am aware that some of my facts conflict with the policies of this state and others; In my opinion, they are assuming that many people cannot differentiate what oak species they intend to transport. I, on the other hand, know many can. Those that don’t care will move whatever whenever, so those that do care should be given accurate specifics and be the judge of their own knowledge level.

- Live Oaks do NOT form fungal mats. Period. Live oak lumber, firewood, etc. is always safe.

- Bur Oaks form fungal mats! Period. There may also be other white oak species in Texas that potentially can as well. There has been zero testing of this possibility. Therefore, encourage the testing and do not move any other oak wood but live oak that hasn’t cured for a couple of years until testing is performed.

- The concern is NOT just firewood – it is any wood product, lumber, etc. of potential mat-producing species that are dangerous.

- If you are not 100% certain of what tree species wood you want to move or how long the wood has cured – then do NOT move it. At all. Ever.

- Some states and countries and continents have moratorium on all things oak – good for them. Many more should follow suit until we can 100% guarantee no transference is possible. For those that don’t care, I strongly suggest laws be made an enforced that pack enough punch with consequences to cause those that don’t care – to care enough about the consequences to not do it ever again.

- dontmovefirewood.org

Spore Producer (SP) Scouting/Roguing

It is my firm conviction that the lack of attention and formulation on an aggressive plan to eradicate or rogue mat-forming oaks (Reds, Blacks, and Bur), has put us in a much worse predicament. Roguing is an attempt to eradicate inoculum (source of infection) production during the course of the epidemic (oak wilt) by destroying the source(s) of the inoculum. (paraphrased).

There are many facets to the scouting or roguing of SPs. First and foremost, is to identify the recently infected SP. We encourage you to thoroughly review our Identification page, then call us to help you devise a consultation, confirmation, and plan of action. Second, is knowing the likelihood of that tree forming spore pads and when they will likely do so in order to effect the control measure best for that tree. Third, is employing one of the following control measures. The easiest and cheapest control measure that should be employed immediately is the use of herbicide to kill and dry the tree. This method is likely most effective on new SP infections that occur in Spring and Summer. In my estimation, a Late Summer/Fall infection application of herbicide may not effectively stop spore production. Another control measure is the removal of a tree at ground level and burning it prior to the formation of pressure pads. Another control measure is to chip the felled tree or to flail the tree as it stands without felling it. Herbicide should be used on the stump in most occasions. If one is concerned about the possibility of herbicide damage to a neighboring tree grafted with the red oak – here are the facts, yes that neighboring, grafted tree should die as well because if herbicide can move to it then the fungus surely will too. This brings up one of the key points of my Spread page, namely that inter-species and intra-species grafting is much more common than the TFS stated likelihood. Herbicide is like a litmus test – and when employed it confirms quickly what I see in oak wilt centers over an extended time. It is rare for any Red oaks, Blackjack oaks, Lacey oaks, and Shin oaks to dodge infection – at most I see delays but the eventual transfer is normative. Fourth, this being the case – though I do not necessarily recommend pre-emptive removal of the probable future SP’s, I do know that they must be watched and one should anticipate their eventual succumbing to infection as well as destruction efforts.

I recommend all ranchers, cities, neighborhood associations to employ expert scouts at mid-Spring, mid-Summer and early Fall to catch SP’s in active wilt. In HOA’s and municipalities, there must be laws and policies in place that require a control option to be selected and consequences if action isn’t taken, as well as funds in reserve to make that happen if the property owner is unable.

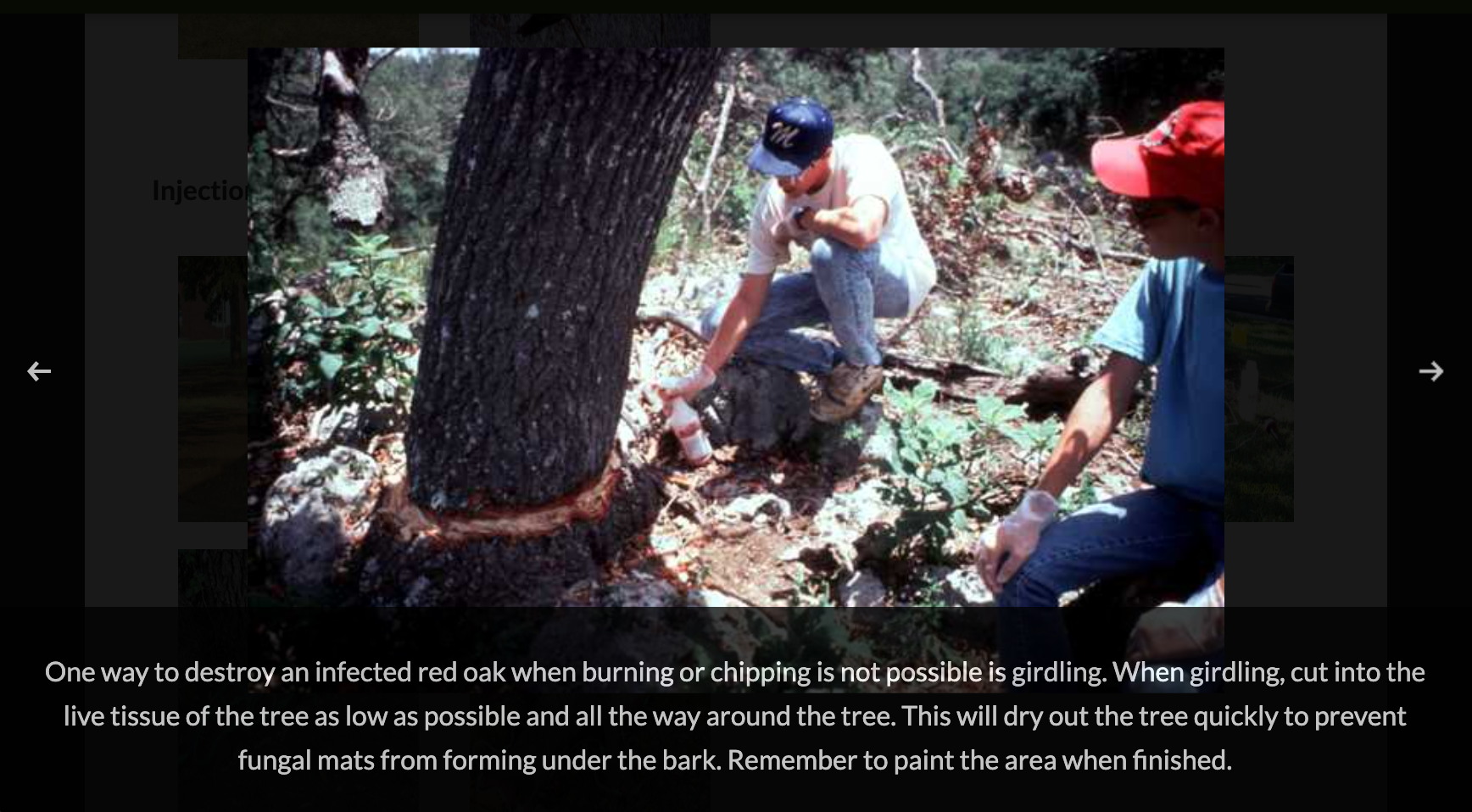

For whatever reason the TFS failed to include in their description of this photo the most integral component of what was actually being done, which was girdling the tree in order to apply herbicide that was in the spray bottle in the guy's hand in the picture. Also, it is quite perplexing that a recommendation is being made to paint the girdle on an already infected red oak. The pain is to protect uninfected oaks from the disease. Even more confusing is the need to spray herbicide on the girdle but paint either prior to or after the herbicide application would cause efficacy issues with the herbicide application.

Kevin Belter, "Oak Wilt Prevention 101," ISAT Newsletter: In the Shade, June 1, 2020, 6.

Pruning/Wound Sealing

The TFS has a strong and laudable message here. I will suffice to add that natural wounds often occur and that their message does not adequately address this fact and that a large number of oak wilt centers occur as a result. In lieu of this incontrovertible fact I suggest statements like,

“Prevention is easily accomplished by immediately painting wounds to oaks and not pruning oaks during the spring.”

***Update: TFS has deleted the “easily accomplished” part – now they need to contact all the people who ran with the previous message they had and request them to change the public message.***

The TFS still needs to adjust language about the ease of prevention. See below:

“Oak wilt is easy to prevent…”

https://aggie-horticulture.tamu.edu/plantanswers/trees/oakwilt.html

“Personally, I’ve never lost sleep over oak wilt because it’s so easy to prevent. Never prune in the spring or fall and always paint the cuts.”

be completely retracted and attempts made to find and re-instruct those misinformed by the prior statements. Prevention is NOT easy! We are losing this battle in Texas big time! Under-estimating the adversary and the complexity and effort in fighting oak wilt effectively will only get us more of what we’ve already got.

One should keep in mind too that, human activity could for example be the obsession of removing all agarita, persimmon, and other brush away from every small oak – that allows for the deer to easily and happily rub the now easily accessible exposed trunk – it is not always a result of deliberate pruning! Dealing effectively with varmints, deer rubs, and grabbing a paint pole each morning after strong winds to paint wind breaks should also be stressed just as strongly in their painting campaign.

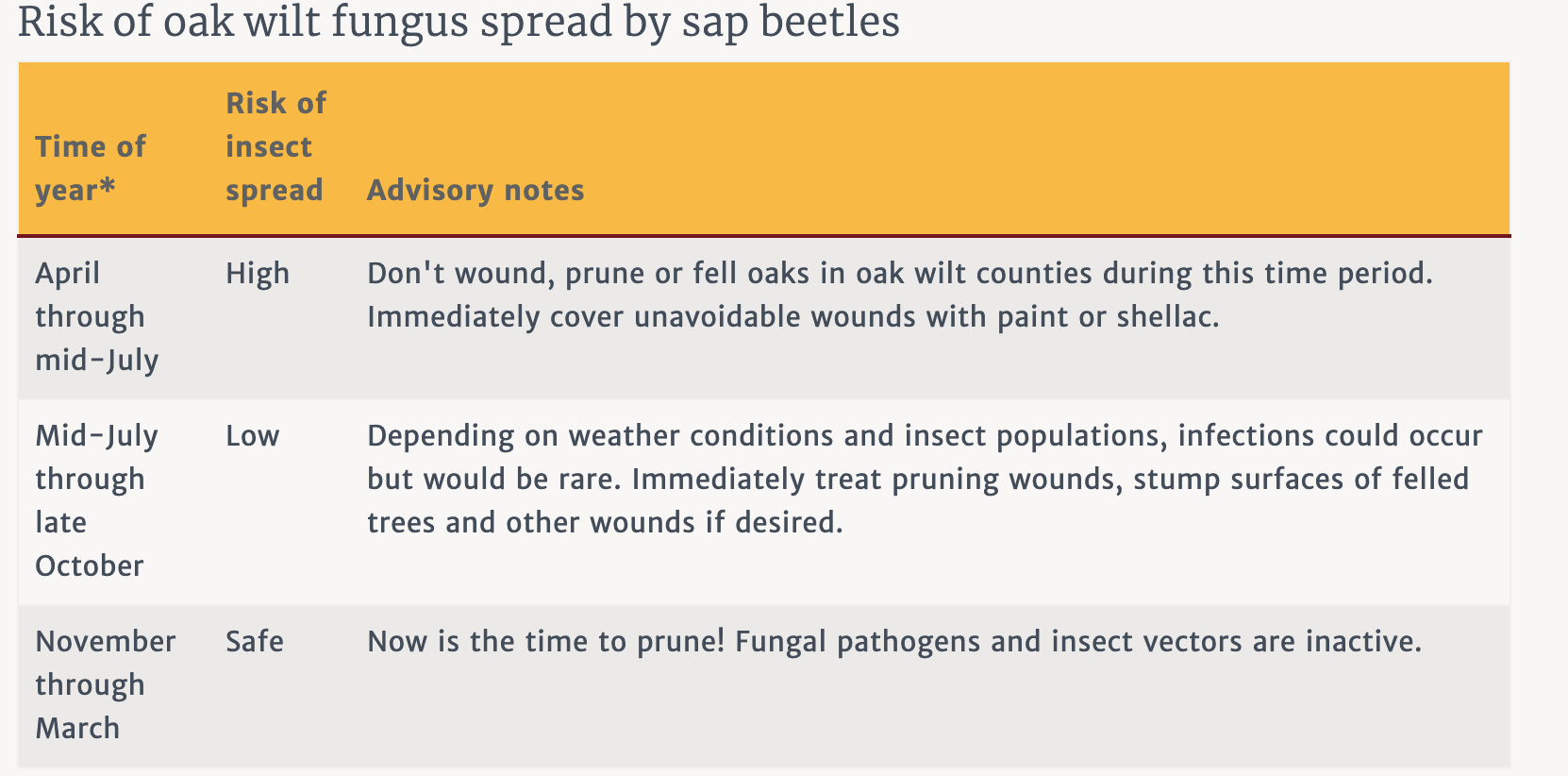

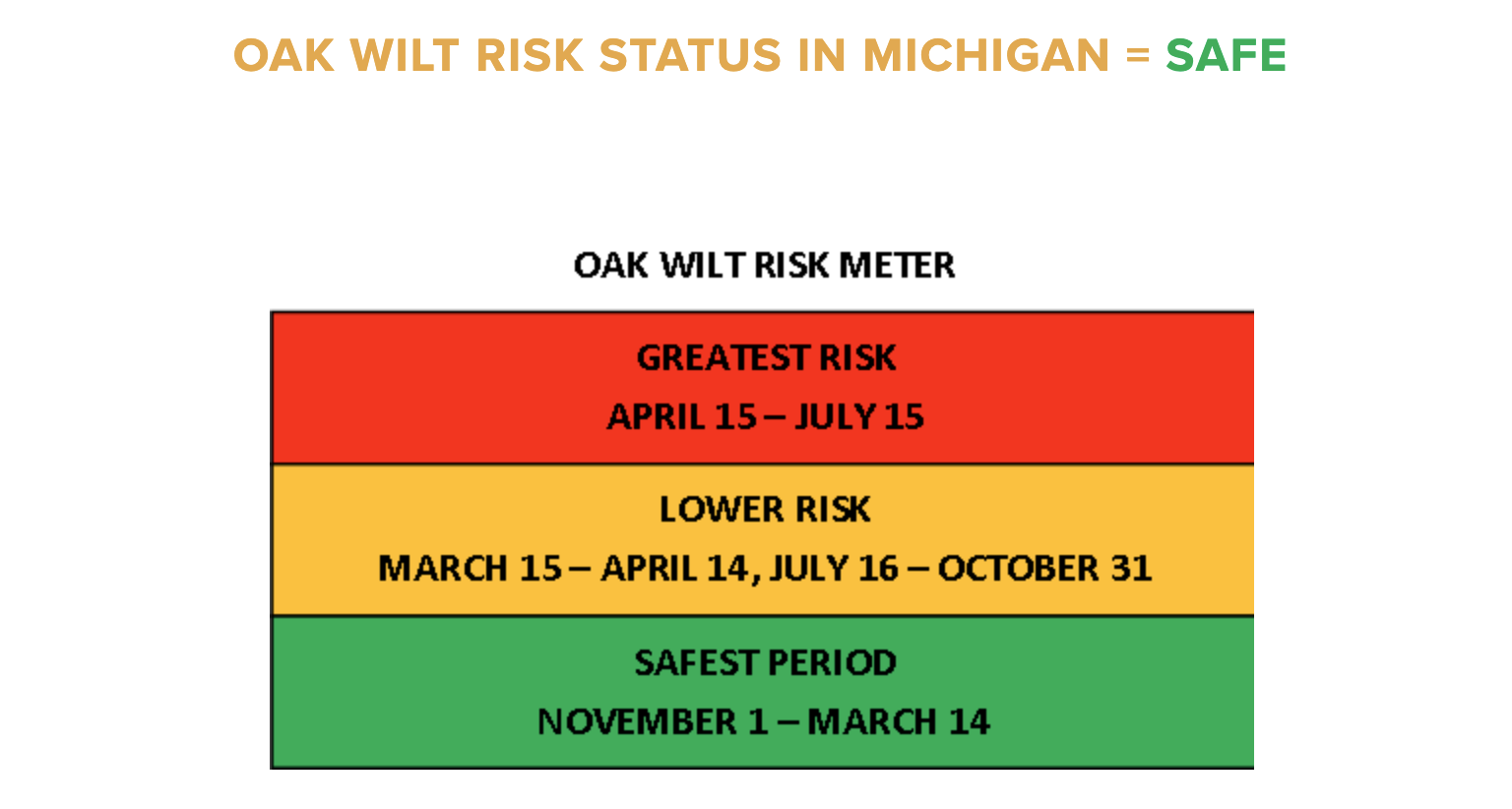

The number one absolutely wrong and reckless and unbelievable failure of the northern experts is the abstention of painting during the “low-risk” and or “safe” months. Any risk at all is worth the application of paint. There is no tree health consequence from painting wounds that can even come close to comparing with oak wilt. Absolutely irresponsible. I am aware of one expert who received retaliation from those who are promoting that there are no fungal mats nor nitidulid beetle activity from Oct. 16th - March 14th yet he had found and documented the exact opposite. I have access to that proof – it is definitive and sobering. Their oak wilt pruning risk calendar is as follows:

I am very grateful that here in Texas we are strongly admonished to paint all year long – now if only the TFS could add to their campaign that oak pruning is never safe and that to ask “When is it safe to prune oaks?” is just the wrong question.

Fungicide

The use of fungicide in the battle against oak wilt is commonly referred to as “chemical control.” I don’t prefer that word choice because I think that it can be confusing when employing two radically different types of chemicals in this war on bretziella fagacearum: one – fungicide, gives life while the other – herbicide, takes life to spare the lives of many others. We will look at the three types of fungicide application methods and discuss the pros and cons of each. We will also look at the topics of assessing which oaks are “high value” and which ones are not, injection timing, dosing, low vs. high disease pressure, injection technique, prophylactic and therapeutic treatments, number of treatments needed, product choices, and a very interesting and promising additional way to even more effectively treat with fungicide.

High-value trees is an admittedly subjective designation when it’s all said and done. Objectively, it would most consistently be defined as otherwise healthy, structurally sound, and contributive trees overall to canopy cover, aesthetic beauty, long-term property utility that are 10+ inches, and lastly, don’t serve as a “signal or flare tree” (proprietary practice associated with single-injection approach). Timing is critical – especially with a standard single-injection per tree approach. Full product efficacy is only up to one year – but in multiple growth ring years, one ideally needs to be able to identify when that tree will be challenged within 6 months or less. This requires the monitoring and consideration of many factors by the tree caretaker in order to achieve an accurate timetable per each tree. I am often asked what the best time of the year to treat is. Though it may sound dismissive – the truth of the matter is honestly always right prior to infection. I will say it is my professional opinion that the ideal time to prophylactically treat would be in the fall or winter for Live Oaks and the fall (pre-leaf drop) for the deciduous white oak species, wherein there is a greater distribution of the fungicide into the root system – almost equaling distribution equally below and above ground. The best time for therapeutic treatments would be in the Spring as it is the best time for a declining tree to still distribute and that distribution is almost entirely upward where the tree needs it most to kill the already aggressively colonizing fungus.

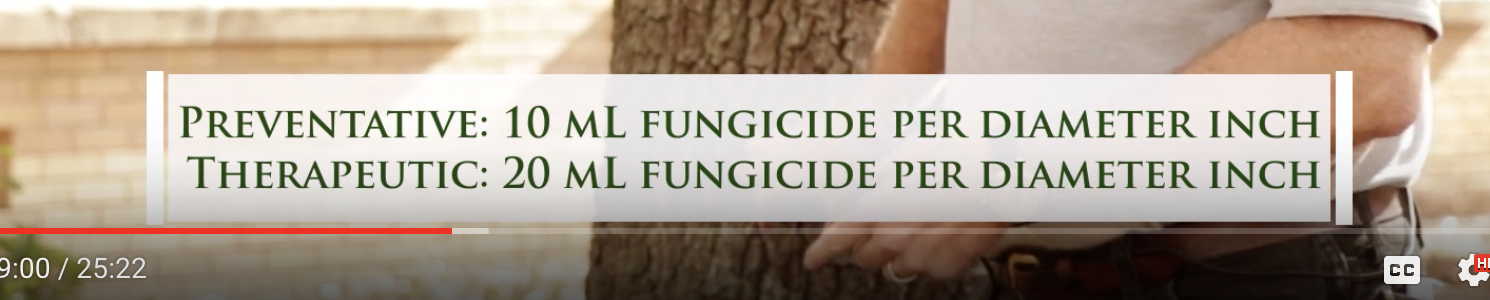

Due to the seasonal distribution tendencies as well as compounding issues such as extreme heat and drought – the same tree often cannot be treated with the same dosing amount any given time of the year. Fall and winter dosing can be the highest followed closely by spring and the heat of the summer requires a lower dose. Sound like it’s getting pretty complex? Now enter in the estimation of tree mass as the ultimate base line for the consideration of the 10-20ml of propiconazole spectrum per DBH. One 10” DBH tree may be 30’ tall and a full canopy and another on the same property may barely be pushing just under 15’ and next to another so it only has half a canopy. Two 10” DBH trees are not always the same size – you cannot dose them the same.

On the subject of re-treatments and are they needed. Unlike the TAMFS who suggests that two treatments are needed - I will resist the over-generalization impulse that unfortunately plagues that agency and I will opt to discuss the facts with you. The facts are these - there is low and high pressure oak wilt and propylactic and therapeutic treatments. As to low vs high pressure - this is due to many factors but most especially the dna of the particular oak wilt strain affecting your trees, and a distant secondary factor would be the photosynthetic rate and capacity of the tree being challenged. As to pre-infection treatments vs thereapeutic - after infection treatments tend to need additional treatment, while a low to medium pressure oak wilt you often dont need an additional treatment. Some like the TAMFS may say when in doubt do it twice cuz sometimes it is actually needed but but the truth is that it may not be needed and to some that reduction in economic losses is very important. I will suffice it to say that if the contractor cant or wont discuss the minute details with the tree-owner - they may not be the right one to assist in formulating the right fungicide management plan.

“OAK WILT: Preventive and Therapeutic Treatment:

Use 10 ml of Alamo in up to 1 liter of water per inch DBH. For very high disease pressure, 20 ml of Alamo per inch DBH may be used.”

Here we see that the rate of dose of the fungicide is dependent upon disease pressure (low to moderate to high) – not upon whether it is prophylactic (what many erroneously call "preventative") or therapeutic. Actually when considering mass of tree and rate of dose – it is imperative that the likelihood that the solution will mostly move to still photosynthesizing portions of the tree. This will actually cause the portions of solution meant for the non-photosynthesizing tree parts to go to those sections and causing an over dosage and probable phytotoxicity event and likely mortality. How does one determine disease pressure? That is a complex question! Size of trees, quantity of trees, proximity of trees, soil quality, soil moisture content, and various other factors all play a role. It is best for an experienced arborist weigh all that – suffice to say not all arborists are equal and not all arborists have trained applicators further causing need for choosing the contractor carefully. A final comment regarding therapeutic treatments – if a tree is very high value but sick, it is important to know that if using current iterations of propiconazole - it may take a few days and maybe even a second drilling event to save the tree. Most contractors will pull the tanks on day one – but maybe a rare few contractors will even leave it two days (almost certainly unattended during the day)– but if it has taken say half the product on day one and say it will take another 30% on day two and another 20% on day three – that complete uptake may very well be the difference between success and failure.

Here are a few techniques and corresponding research that help us better treat your trees.

1. Heavy, thick, or loose outer bark may be carefully shaved to form a smoother injection point and to ensure the operator that the drill hole penetrates through the bark to the xylem.

2. If the flare roots are not clearly exposed, carefully remove 2 to 4 inches of soil from the base of the tree to uncover the top of the flare roots. Brush away loose soil.”

3. "…Space injectors 3-6 inches apart around the base of the tree. Do not drill in the valleys between the flare roots or into cankered areas. Drill above these areas into the trunk, then continue again into sound sapwood on the flares.”

Couple of things I’d like to point out here:

It is recommended to shave bark, put at top of root flare NOT into the roots, to drill into the trunk area for numerous reasons – not skip from root injection to the next root, 3” depth is an appropriate distance between injection points, and finally into the flares again – not into the roots. Top-level current researchers of tree physiology have definitively moved away from the old delineation between the trunk flare and root flare. They now speak of them both as all one transition zone or use them interchangeably – “root flare also known as the trunk flare…”

“root flare: see trunk flare”

“trunk flare: transition zone from trunk to roots where the trunk expands into the buttress or structural roots. Root flare.”

https://wwv.isa-arbor.com/education/onlineresources/dictionary

“trunk flare: transition zone from trunk to roots where the trunk expands into the buttress or structural roots. Syn. Root flare.”

Best Management Practices. TREE INJECTION. Shawn Bernick & E. Thomas Smiley, PHD. ISA, 2015.

"Root flare or trunk flare: The area at the base of the plant’s stem or trunk where the stem or trunk broadens to form roots; the area of transition between the root system and the stem or trunk."

https://www.tcia.org/TCIAPdfs/business/GISD.pdf

“flare: the transition zone where the trunk flares out to meet the buttress, main, or structural roots. It was also called trunk flare, stem flare, root flare, or first order lateral roots, but these terms are falling out of favor.”

http://gibneyce.com/arborist-dictionary.html#T

Lastly, I’d like to briefly mention some specific facts about specifically Red, Live and White oaks. Regarding red oaks - fungicide can and does definitively stop the formation of fungal mats and if treatment is prophylactic it can keep the Red and Black oak family trees alive. The downside is that treatments must be ongoing to maintain both the tree alive as well as likely insure the formation of fungal mat after the fungicide wears off .

“Propiconazole injection is effective at preventing the production of fungal mats. No fungal mats were formed on oak wilt-killed red oaks treated with propiconazole but were observed on untreated trees (Osterbauer and French, 1992). No infected black oak treated with propiconazole produced fungal mats, while all infected but untreated trees produced at least one fungal mat(Johnson, 2001).”

Live Oaks:

“All treated live oaks showed significantly less crown loss and only 9% mortality when compared to untreated controls (70% mortality) (Appel and Kurdyla, 1992). In a check of 383 live oaks preventively treated with propiconazole in Texas 1–4 years earlier, 74% of trees still had 30% defoliation (Billings et al., 2001).”

White Oaks:

“From the available data, preventive treatments of white oaks seem to be nearly always effective. Five years after preventive treatment with propiconazole, only 1 of 26 white (Q. albaL.) and bur (Q. macrocarpaMichx.) oaks showed symptoms and all trees survived the natural advancement of the infection front (Eggerset al., 2005).”

“White oaks infected with oak wilt respond well to therapeutic treatments and such treatments are usually effective at delaying symptom development and extending the life of a tree. Bur and white oaks with 5–45% crown wilt were treated with propiconazole and 87% of bur and 71% of white oaks showed no new symptoms 5 years after treatment (Eggers et al., 2005). Oster-bauer et al. (1994)treated bur and white oaks therapeutically with propiconazole and found that 1 year later, 81% of treated trees showed no increase in wilt symptoms and exhibited significantly less crown wilt than untreated trees, of which 86%wilted completely. Therapeutic treatments of white oaks are so effective that professional arborists rarely treat white oaks with propiconazole until symptoms develop (Eggers et al., 2005).”

https://www.nrs.fs.fed.us/pubs/jrnl/2010/nrs_2010_koch-k_001.pdf

(all four quotes)

Macro-Infusion

(the industry standard delivery system & flagship product)

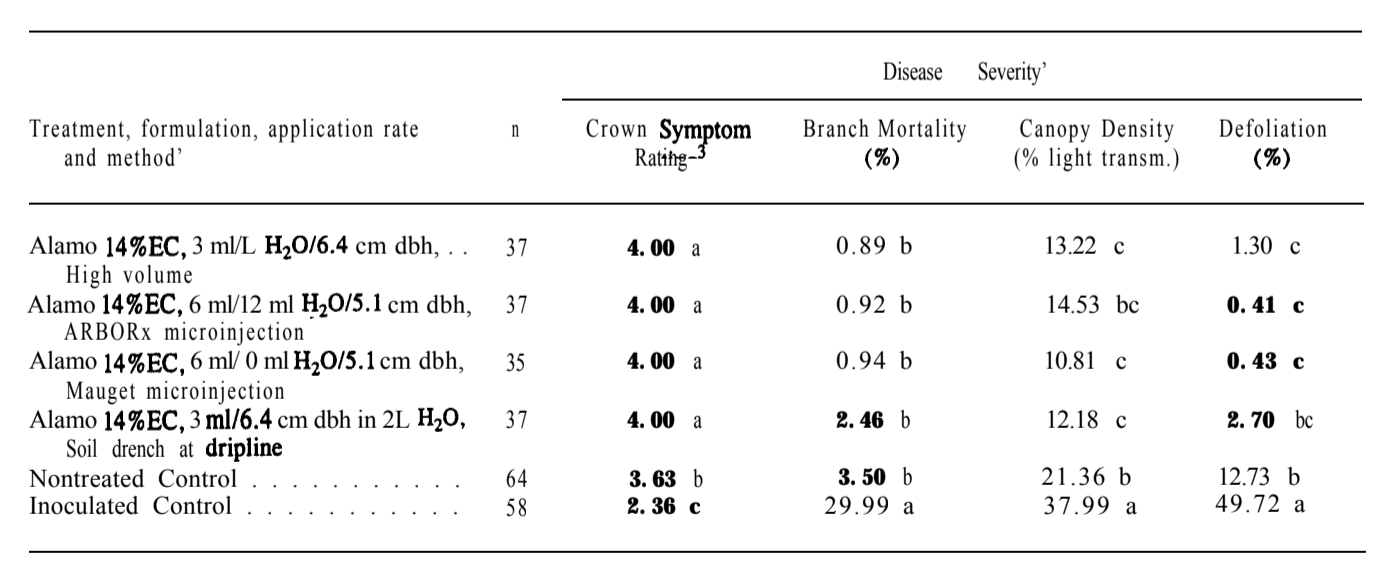

Think of this method of administering the fungicide as akin to an IV drip system. In many if not most cases this is a preferred method for administration whether to a person or in this case – to a tree. Assuming a mature tree is healthy – no other method will distribute the fungicide as effectively or quickly. Though this method has the highest number of drill holes as compared to the other two – those wounds are not a serious threat to the tree. In a question of benefit vs. consequence – the minor wounds are 100% worth the benefits of the macro-technique. This technique has hands down the most research behind it – even stacked or duplicated research by multiple researchers who all came to the same conclusions.

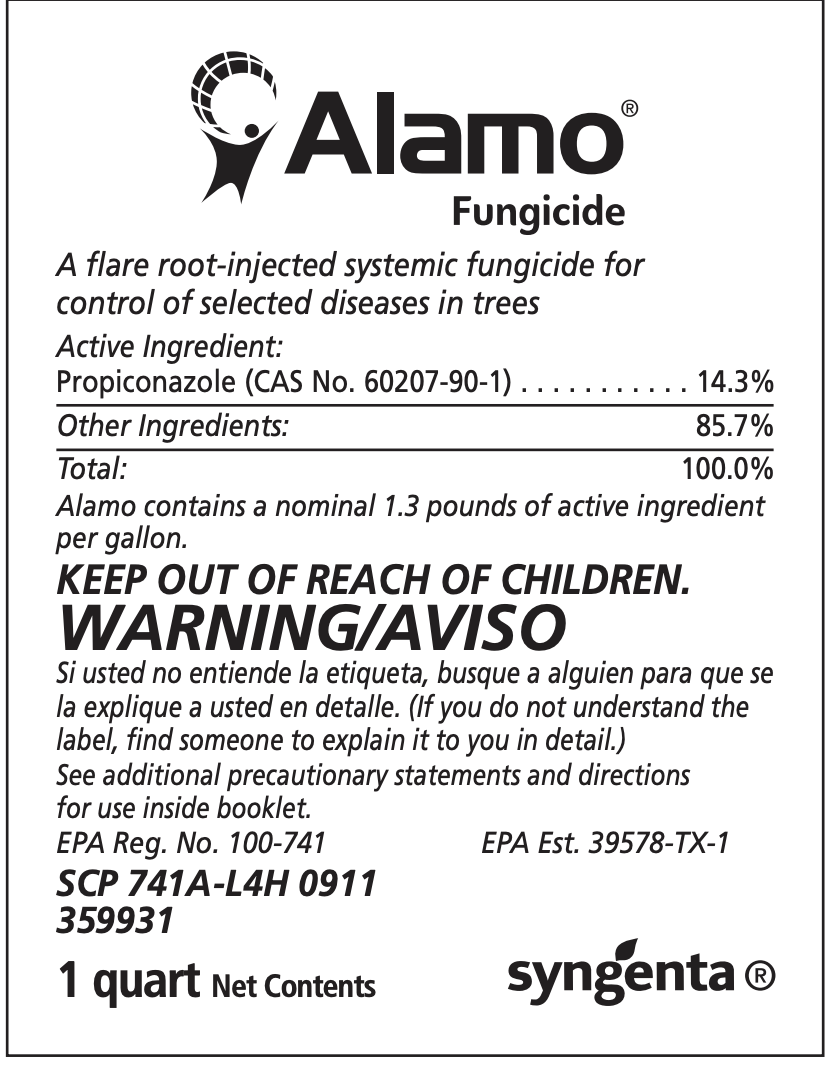

The best product for this method is ALAMO fungicide made by SYNGENTA (Propizol is now also made by Syngenta). It is the flagship product. After the patent time was up – the copycat generics came in. Syngenta continues to improve its product. The generics are not leading the advance. It is my professional assessment that the quality of the active ingredient propiconazole is less consistent in most of the generics as well as the inert ingredients are not identical nor as consistent in their mixes. Currently many of the arborists have switched to the generics to increase their profits. Details matter, therefore I don’t use them. I won’t use them. You should demand for Alamo fungicide macro-injection when you have mature trees in full leaf needing prophylactic treatment. A last word on Alamo – for this die-hard Texan who hails from just a two day horseback ride northwest of the old mission, the name is quite apropos. We are utilizing this weapon of war against the disease as the last stand of defense against the disease. We are choosing to stand and fight as did the defenders of the Alamo. We are not surrendering hope. Though we may not win every battle – we must not give up!

Superior results require superior equipment. Rainbow Treecare Scientific not only has the sole distribution rights of Alamo – they also are the sole distributors of the best macro-infusion equipment on the market. The manual macro-infusion pump is a solid single cast tank. I have tanks that I bout over 10 years ago still in production. The remaining parts are replaceable in the periodic event you work them heavy and need to make the occasional repair. We keep them clean, use oil and silicone as needed all of which ensures our investment is long-lasting and profitable so we don’t need to raise our price to the customer. They hold up to 14 liters, which covers up to the typical mean DBH of trees encountered. There is a view window in the base so you can monitor when the tank is almost empty.

The orange tees in addition to the tip feed of the solution also have side solution distribution ports on both sides in order to supply the solution to all the cambial tissue! One side also has larger side flow for the occasional need to evacuate debris that inadvertently gets into tank and or lines. The other generic tees only have tip feed. I can’t stress enough how important every advancement in solution distribution is.

The orange tees in addition to the tip feed of the solution also have side solution distribution ports on both sides in order to supply the solution to all the cambial tissue! One side also has larger side flow for the occasional need to evacuate debris that inadvertently gets into tank and or lines. The other generic tees only have tip feed. I can’t stress enough how important every advancement in solution distribution is.

Micro-injection

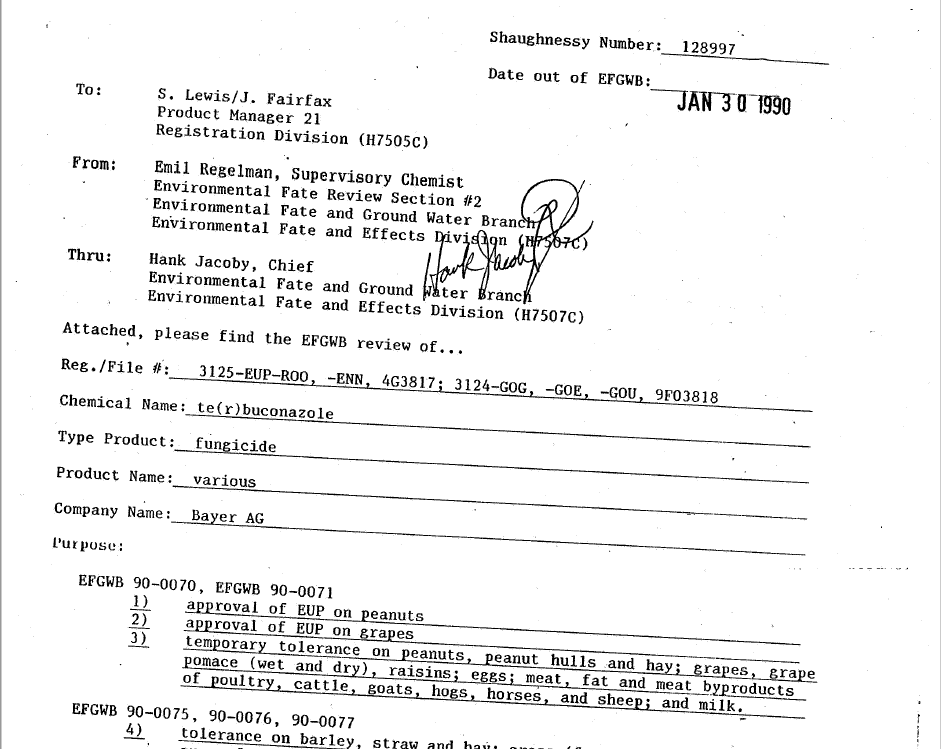

(low-pressure, passive delivery)

Micro-injection is an important tool in our treatment tool box. Specifically, the Mauget product Tebuject 16 HP. We utilize this product (which is a high quality triazole family fungicide called tebuconazole) for trees too sick for macro-uptake, all small trees (less than 8” DBH - due to lower phytotoxicity of Tebuject 16 HP), re-treatments, and for leafless trees needing fungicide but don’t have photosynthetic draw. Very importantly we apply this product at the rate of absorption of each individual tree. Mauget was the first micro-injection manufacturer/injector company. Their products are research-tested.

Micro-Injection

(high-pressure delivery)

We do NOT use this method

The most popular micro-hybrid systems which among other things, seeks to decrease labor costs via use of tree injection devices capable of up to 120 psi, which force the fungicide into the wood at rates that many times over exceed the actual absorption rate of the tree. This type of a delivery system typically recommends employing some form of septum or plug to be installed into the tree to contain the explosion of product occurring into the tree’s vascular tissue. For the discerning consumer who values scientific feedback on the possible risks of these high-pressure injections I encourage them to read the results and discussion section of this very recently published (2020) research thesis:

For those that would prefer the cliff notes version – a high-pressure injection system using permanently inserted plugs (that is becoming more popular for use in commercial oak wilt treatment), during drought conditions consistently caused significantly more external bark cracks, longer bark cracks, more internal sapwood discoloration (both in volume and area), and a decrease in wound closure as compared to the macro-injection method of Alamo. A premier, experienced applicator who represents and sells this high-pressure system performed the injections. The ISA BMP on Tree Injection repetitively warns about damage from improper plug setting, hugh pressure application dangers and definitively states: "If uptake time is sufficient and the product does not leak out of the unplugged hole, then there is no benefit to using plugs." (pg. 28).

The burden of proof is on these new delivery tree injection systems to compare both their effectiveness as well as negative side effects with the already proven method in use. The cart was put in front of the horse here and the impacts of high pressure and permanent plugs are being researched slowly after the fact. This is an unfortunate situation but important for those tree owners to know who are facing the dilemma on which is the best way to have their trees treated. I strongly urge the manufactures of these high-pressure systems to conduct research on their systems to see the full range of damage caused by their system across species and various psi settings during drought conditions (practically the norm in Texas!) and then present that peer-reviewed research as part of their marketing approach as did the macro-infusion & Alamo marketing campaign did some 30 years ago. Finally, unless they can prove better results than plug-less systems - the plugs should just be abandoned entirely.

Additional Experimental Method

Below is an excerpt from Dan Wilson with the USDA Forest Service Southern Research Division, which discusses improved formulations of Alamo as well as field trial data, which provide clear and convincing results warranting further studies of this promising method both combined with flare-injection and without flare injection.

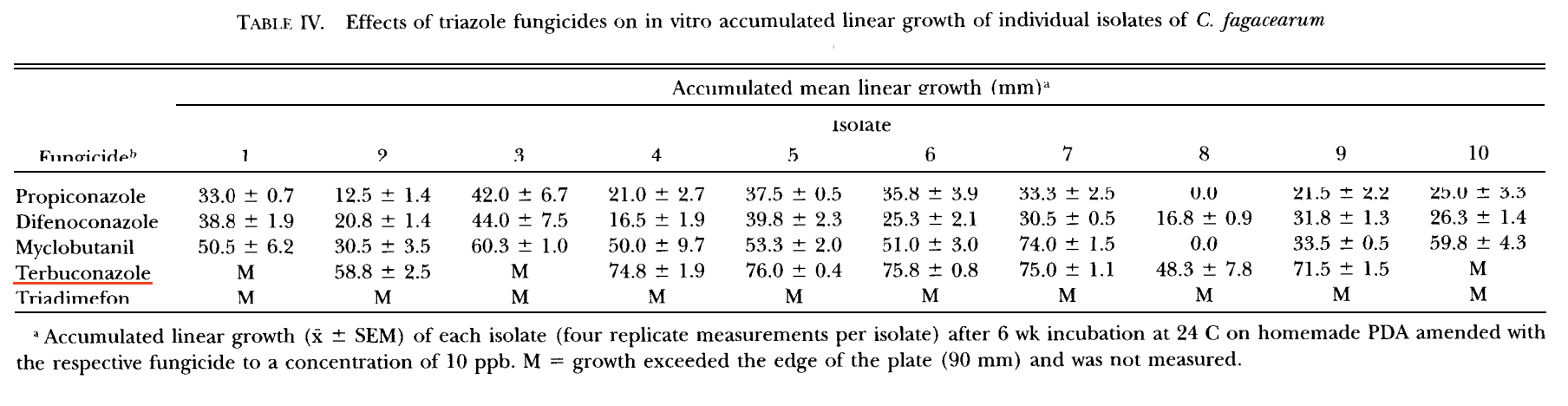

“The problem with propiconazole treatments is not the fungicide since the oak wilt fungus is highly sensitive to triazoles in the 10-200 ppb range. The ineffectiveness of fungicide injections is largely explained by the predominantly upward movement of triazole fungicides such as propiconazole (Alamo) in the vascular system of injected plants. Thus, fungicide injections are ineffective in preventing root transmission because the fungicide does not come in contact with fungal inoculum in the roots. Thus, insufficient quantities of fungicide are translocated down into the root system to prevent viable inoculum from being translocated through root grafts into adjacent non-infected trees. Applications of propiconazole as a chemical control to prevent root transmission could be modified so that the material is introduced at the distal ends of the root system, as with soil application treatments. The most effective results with propiconazole are achieved when it is applied annually as a soil drench within the dripline of the tree and over several consecutive years, immediately prior to challenge by C. fagacearum through root transmission (Wilson, unpublished data).

Propiconazole injections should be effective in preventing root transmission if adequate application methods are used that provide thorough treatment of the root system. Efficacy tests of new fungicide application methods using tracker dye in the fungicide solution have suggested that some of the fungicide moves down into the root Some basipetal movement of the fungicide into the root system seems necessary to explain any level of control since the bulk of the inoculum resides in the roots and lower bole. However, any downward movement probably can be attributed primarily to vapor phase activity rather than symplastic movement in the phloem since triazoles with sufficient vapor pressure such as propiconazole, etaconazole and triadimefon are well known for exhibiting vapor phase activity that generates biologically effective concentrations beneath the area of application. Consequently, limited basipetal movement could explain the 50% success rate since such very low concentrations of propiconazole are needed to inhibit growth of the oak wilt fungus. The success of TFS field foresters and certified Texas arborists in protecting uninfected live oaks by propiconazole injections have improved somewhat in recent years. The improvement is related to changes in the formulation used and in the application rates allowable on the Alamo label. Previously, the xylene-based (yellow) formulation was used. This formulation was replaced by the water-based, microencapsulated (blue) emulsifiable concentrate formulation that does not separate when diluted with water and causes fewer phytotoxic effects on callus regeneration at injection wounds. The microencapsulated formulation is more miscible in water and appears to be more effectively distributed in the tree. The allowable rates of application specified on the label also were changed recently from 3-5 to 6-10 ml L-'. The doubling of the legal application rate probably does not change the proportion of the total material that moves into the root system, but it may allow a greater amount of the fungicide to move down by vapor phase activity since more active ingredient is present and available within the tree at each injection port.”

Trenching

National View

“In the Lake States, where deep and sandy or loamy soils are common, using a vibratory plow with a 5-foot blade (figure 8) is the preferred method of disrupting grafted root systems. The vibratory plow consists of a mechanical shaker unit with an attached blade that is pulled behind a tractor. The blade penetrates to a depth of about 5 feet, and cuts through the roots of oaks that may be grafted together. While oak roots may extend deeper than 5 feet in the soil, most root grafts are disrupted by trenching or plowing to that depth. Standard trenching tools do considerably more damage to the site, and the result is a much more apparent plow line than that caused by the vibratory plow. In Texas, shallow, rocky soils and even-layered rock often necessitate the use of a rock saw for disrupting oak roots. A chain trencher, backhoe, or ripper bar can sometimes be used. Trench depth should be about 5 feet, although this may be difficult to achieve in all situations.” (How to Identify, Prevent, and Control Oak Wilt)

Texas View

“Measures can be taken to break root connections between live oaks or dense groups of red oaks to reduce or stop root transmission of the oak wilt fungus. The most common technique is to sever roots by trenching at least 4 ft deep with trenching machines, rock saws, or ripper bars. Trenches more than 4 ft deep may be needed to assure control in deeper soils. Correct placement of the trench is critical for the successful protection of uninfected trees. There is a delay between the colonization of the fungus and appearance of symptoms in the crown; therefore, all trees with symptoms should be carefully identified first. The trench should be placed a minimum of 100 ft beyond these symptomatic trees, even though there may be “healthy” trees at high risk of infection inside the trench.” (See Link)

Regarding depth, I concur with the trench depth of 5ft. as specified by the USFS. Here in Texas the success rate of 4ft. depth at 100ft is averaging somewhere in the 74% range for the “random” evaluation time period which has ranged from (very briefly) all trenches every year to random evaluations for 3 or 5 years (Post Suppression Evaluation or PSE) and is currently random PSE’s for 5 years but only performed every other year. Assuming that 74% is an accurate number – what this statistic tells me is that about ¾ of the time all the roots were likely severed at that depth and the trench was far enough out. The other 25% failure occurred because not every root was cut or the trench was not far enough ahead of the actual infection zone. It is my professional opinion that the increase to 5ft. minimum would likely get that statistic to about 85% (for up to five years). The remaining trenches that fail need an excavation machine paired with an inspection of trench wall for root stoppage - in most cases 8-12ft. It is important to add that in some areas porous rock structure (ex. Karst geology) would warrant a complete rejection of the trenching option in favor of a silvicide approach. An important point to consider is that with only $1000.00 max cost share which is approximately the price just to get a machine to your site, often times the only trenches being selected for actually installing these days are those ones highly probable to succeed at cutting all the roots to 48”. That leaves a lot of mortality centers unattended to – where roots are too deep or rock is too hard for machine or where topography prevents any machine access.

Next topic to consider is breakout trenching, which is uncommon up north because of their dual barrier lines, roguing and herbicide protocol they often utilize (see sections below). Breakout trenching in Texas is historically 25% percent of trenches within the first 3-5yrs. on account of not severing all the roots. All later occasions are almost certainly due to re-grafting of roots between the infected trees and the healthy side trees but there is no official data as the TFS does not do Post Suppression Evaluations (PSE’s) after 5yrs

Dan Wilson with the USDA Forest Service Southern region, is one of the great minds in oak wilt research. When I reference his coverage of topics – I have little to no need to make additional comments. I rely on his writing heavily in this section.

“However, breakouts that occur during and beyond the third year after trench installation are probably due to inoculum passing through new root connections forming across the trench from anastomoses of newly formed roots. The reason for this delay in root grafting across trenches is that the process of root regeneration within trench backfill soil takes at least 3-4 years after roots are cut by trenching before it is sufficient for root grafting. Small adventitious roots less than 1cm in diameter commonly form from the ends of lateral live oak root branches severed by trenching. These small roots grow and accumulate within the trench in the loose backfill soil, which favors root growth relative to the hard, compact undisturbed soil.” (See Link)

What follows are three critical passages taken from an abstract Dan Wilson with the US Forest Service Southern Research Station, presented from during the 2007 Second National Oak Wilt Symposium:

“Most oak wilt specialists acknowledge that the formation of new root grafts across an oak wilt suppression trench may eventually occur, leading to a breakout some years after a trench is installed. In the author’s opinion, this phenomenon is not only common but increasingly prevalent three years after trenching, even in dry sites, especially for Live Oaks that have such a strong propensity to form root grafts in the shallow soils of central Texas. Oak roots in this region on the Edwards Plateau commonly grow through layers of limestone permeated by pockets of soil. Soil usually fills holes in the rock formed by the percolation of groundwater through the limestone. Nevertheless, the limestone rock bed layer tends to restrict and concentrate oak root growth above it, increasing the chances for root graft formation between the roots. In this situation, trenches alone are not intended to provide long term protection against root transmission because new root grafts are expected to form over time between these concentrated roots that grow within trench backfill soil” (pgs. 211-12).

{second excerpt}

TRENCHING EFFECTS ON SOIL STRUCTURE AND ROOT INTERACTIONS

The first essential information needed for improving trenching technologies for control of this disease is to determine why trenches fail or why trench breakouts occur. The principal reasons why trench breakouts occur usually vary with time after trench installation. Breakouts that occur within two years after trenching usually result from placing the trench too close to the infection center or not trenching deeply enough to sever all roots. Breakouts that occur after 2-3 years are likely the result of root re-grafting across the trench. Trenching causes changes in the physical properties of soil structure and subsequent root interactions that occur in trench backfill soil after trenching. These effects of trenching on soil structure and oak-root interactions set into motion a dynamic process that ultimately increases the chances for trench breakouts over time following trenching.

PROBLEMS WITH TRENCHING

One of the biggest problems associated with the mechanical cutting of trenches for oak wilt control involves the effects of trenching on soil structure and characteristics within the trench. Trenching creates a soil environment highly favorable for root growth. Farmers till the soil in their fields before planting for this very reason. Tilling the soil reduces the bulk density of soil by breaking up soil aggregates into smaller particles, rendering the soil friable and more favorable for root growth, penetration by rainfall, and infiltration by fertilizers and nutrients. For the same reason, no-till cultivation has been adopted as a farming practice in many areas of the U.S. to reduce soil erosion and weed growth stimulated by the loosening of soil structure that facilitates root growth of competitive weed plants. Trenching has the same effects on soil structure as tilling the soil. Backfill soil within the trench is loosened significantly (bulk density 1.22 g/cm3) relative to the compacted surrounding soil (bulk density 1.62 g/cm3) (Backhaus 2005). There are several consequences that result from these changes in soil structure due to trenching. Roots from the surrounding compacted soil seek to grow in this loose backfill soil because it provides the path of least resistance for root growth, expansion, and branching. Consequently, roots proliferate and penetrate into this loose trench backfill soil much more rapidly than in the adjacent, compacted soil on either side of the trench. The loosened backfill soil within newly-cut trenches also is a natural sink for water and nutrient flow into the ground, again because it is the path of least resistance. Water and dissolved nutrients tend to collect and accumulate within the loosened trench soil, further enhancing and stimulating new root growth from roots adjacent to the trench. The natural influx of tree root growth into this more favorable trench soil is promoted by all of the improvements in soil conditions that result from the trenching process. The cutting of oak roots by trenching induces the formation of fine (<5 mm-diameter), feeder roots in trench soil due to the loss of apical dominance. This same phenomenon occurs when apical meristems are cut in the upper parts of the tree resulting in the loss of apical dominance and the production of sucker sprouts on trunks and lateral epicormic branches. The production of lateral roots, due to the loss of apical root dominance in roots severed by trenching, leads to the proliferation of fine feeder roots in the loose backfill soil of newly-cut trenches. These feeder roots begin forming within a few inches of the severed ends of roots as soon as soil moisture becomes available. Trenches are generally backfilled immediately during the trenching process, allowing new root growth to begin forming usually after the next rain event. Most feeder roots are found within the top 18 inches (46 cm) of the soil surface where soil moisture is most available following a rain. Feeder roots also form from the cut ends of deeper roots severed by trenching. The very high tendency of Texas live oaks to form root grafts and common root systems allows these species to utilize the ideal conditions within newly-cut trenches to initiate the formation of new fine feeder roots that readily graft with roots of other live oaks with which they come in contact. Because live oaks on both sides of the trench have roots severed by trenching, these trees send out an abundance of new feeder roots into trench soil creating conditions very favorable for the formation of new root grafts across the trench. It is for this reason that the TOWSP recommends uprooting all trees and disrupting or extracting the root system inside the trench in rural areas.

TRENCH BREAKOUTS – WHY THEY OCCUR

The majority (60.1 %) of oak wilt breakouts from TOWSP trenches have occurred during the first two years after trench installation (Table 1), due to factors other than regrowth of roots across the trench (Gehring 1995). The rate of new trench breakouts decreases rapidly over time after two years resulting in negative slope curves for breakouts beyond two years after trenching. Nevertheless, up to 40% or more of all trench breakouts occur after two years following trenching. Even though trench breakout rates continue to decrease after two years, breakouts have been recorded to occur up to fifteen years or more after trench installation, far beyond the time normally expected for C. fagacearum-inoculum to move through existing root grafts across the trench. The expanding edges of oak wilt infection centers are known to move up to 80 feet (25 m) or more per year in Texas live oaks. Because trenches normally are installed within a 100-feet (30 m) buffer zone beyond the advancing front of the infection center, it usually takes a maximum of two or three years for C. fagacearum-inoculum to move through any preexisting root connections that were not severed by the trench. Breakouts that occur after two years are increasingly more likely to be due to transmission of the fungus through new root grafts that formed after trenching (Table 2). The delayed timing of later breakouts is due to the time required for new root grafts to form and provide a route for inoculum in the roots to pass beyond the trench barrier. Most breakouts occurring within the first two years after trenching have been attributed to inoculum passing through pre-existing root grafts either due to 1) insufficient trench depth, 2) insufficient buffer distance set up between the visible (symptomatic) advancing edge of the infection center and the positions selected for trench placement, or 3) a discontinuous trench (Gehring 1995).

Trenches that are not cut to sufficient depth allow the fungus to pass through roots that were not severed under the trench. This occurrence is common where the soil depth to bedrock in localized areas is greater than the depth normally encountered in that area or when soil depth is greater than the depth recommended by suppression-operation criteria. Cutting the trench too close to the infection center, without leaving a sufficient buffer zone, can also be a problem. Trenches placed too closed to diseased trees fail because the fungus has already moved through roots by the time the trench is installed. Discontinuous trenches, often caused by the need to avoid buried utility lines, provide opportunities for inoculum to pass through gaps in the trench where roots were not severed. Obviously, the rates of trench breakouts, due to discontinuous trenches, tend to increase in urban areas. The TOWSP does not cost-share continuous trenches unless the utility lines have been installed at least four feet deep with the past four years. Even though most trench breakouts occurring after two years following trenching occur due to new root graft formation, some breakouts occasionally may occur due to movement of C. fagacearum-inoculum across the trench by insects or other vectors (Table 2). The movement of red oak firewood from infected trees within infection centers to areas outside of the trench also may explain some jumps or gaps in infection patterns in the vicinity of trenches. There is also the possibility that unknown root-feeding or stem-feeding insect vectors may be carrying inoculum of C. fagacearum across trench barriers. Problems of trenching associated with improper trench depth and buffer distance can be largely solved by increasing trench depth when possible and increasing the buffer zones used for determining trench placement. These adjustments have been made several times in the operational criteria used for trench installation in TOWSP operations. Unfortunately, modifications in trench designs and placements do not solve the problem of breakouts due to other causes, particularly the formation of new root grafts in the loose trench backfill soil. Trenches alone are not permanent by design. They cease to become a barrier as soon as new root grafts from across the trench. The very high tendency of live oaks to form root grafts, coupled with the greater incidence of root growth and root graft formation in trench backfill soil, increasingly favors the ability of C. fagacearum-inoculum to eventually move through a new root graft connection to the other side of the trench over time. The actual likelihood that new root grafts will form in the trench backfill soil in any one location is dependent on a number of factors, including weather and rainfall patterns, the presence and density of trees on both sides of the trench, the amount of inoculum-pressure put on the trench (determined by the size of the infection center being contained), the rate of movement of the infection front, the depth of the soil and/or trench, soil texture and fertility, and slope of the terrain. However, the rate of new root graft formation in trench soil is probably most determined by available soil moisture in the trench, the density of live oaks on both sides of the trench, and the depth of the soil in the trench.

These three factors probably have the greatest effect on feeder-root density, and thus determine the likelihood that new root grafts will form across the trench. An alternative explanation has been proposed to explain breakouts that occur beyond two years after trenching. This explanation suggests that these breakouts may be due to insufficient trench depth instead of the formation of new root grafts in the trench soil. The theory implies that roots occur under the trench by which the oak wilt fungus eventually passes, but that the movement of C. fagacearum-inoculum in the roots is delayed by insufficient rainfall, inadequate tree transpiration, or other factors that somehow slow down the movement of inoculum in the root system and delay trench breakouts. The problem with this explanation is that the movement of water carrying C. fagacearum-inoculum in the transpiration stream of roots through root grafts is controlled mostly by the transpiration of healthy trees outside of the trench that pulls water from the root systems of diseased trees inside of the trench. Transpiration rates in the stems of oak wilt-infected trees are slowed due to vascular plugging by the fungus. Consequently, transpiration rates are higher in healthy trees that have no vascular plugging. This is the reason why transpiration water tends to flow mostly away from diseased trees (at the expanding edge of the infection center) toward uninfected healthy trees (outside of the trench) that still have substantial transpiration occurring. This is the only reasonable explanation to account for the often rapid rates (75-150 feet or 23-46 m per year) of expansion observed in Texas oak wilt infection centers. Given this strong outflow of transpiration water through preexisting root grafts, that were not severed between diseased trees at the edge of infection centers and healthy trees outside of the trench, there should be a very low probability that C. fagacearum-inoculum would not pass through one of these preexisting root grafts within the first two years after trench installation. The movement of transpiration water through root grafts to healthy trees can be slowed by drought conditions. However, if there is a root connection path (root graft) around or under the trench for inoculum to pass through, it should occur within two years because movement of transpiration water is analogous to water running downhill by gravity. Healthy trees cannot survive for very long without transpiration. Anything being carried by the water, whether it is dissolved nutrients or C. fagacearum-inoculum, is moved in the transpiration stream and taken up by the roots of healthy trees outside of the trench. Therefore, it is reasonable to assume that breakouts that occur beyond two years after trenching are due to newly formed root grafts in the trench because all old preexisting root connections were effectively severed by trenching. In the absence of an extended drought, the delay in trench breakouts beyond two years is increasingly more likely caused by the delay in formation of new root-connection paths across the trench by which inoculum can be carried to healthy trees outside of the trench. The only other appreciable factor that could lead to a delay in trench breakouts beyond two years after trenching is the placement of the trench significantly more than 100 feet beyond the infection center. In this case, it would take longer for the fungus to traverse the greater distance through connected root systems to challenge the trench. The greater time required before the trench is challenged provides more time for new root grafts to form across the trench, increasing the chances for trench breakouts when the inoculum of the fungus finally arrives at the trench. More evidence for trench breakouts due to new root graft formation is provided under the section Trenching Results in a Metropolitan Area.” (pp. 202-206)

Trench Inserts

{third excerpt}

“A 7-year study was initiated in 1993 to look at the feasibility of improving the effectiveness and longevity of trenches using trench inserts (Wilson and Lester 2002). A significant finding in this study was that small oak feeder roots, formed from roots severed by trenching, grew into the loose backfill soil within trenches allowing new root graft connections to form across the trench. The results showed favorable indications that trench inserts could provide significant improvements in the performance of trenches by preventing the formation of these new root grafts that allow inoculum (conidia and hyphal fragments) of the oak wilt fungus to move beyond the trench. Preliminary research demonstrated the efficacy of trench inserts in stopping the expansion of oak wilt infection centers beyond the trench up to six years after trenching (Wilson and Lester 1996a-c).”

[7-year study]

How to Identify, Prevent, and Control Oak Wilt

In another article in 2010 Jenny Juzwik states,

“VPLs, the length of time for such grafts to form, and the abundance of new root proliferation for Q. rubra and Q. ellipsoidalis following root severing should be considered in future studies, particularly in Michigan, Minnesota, and Wisconsin, where vibratory plows are used in oak wilt control efforts.”

https://www.nrs.fs.fed.us/pubs/jrnl/2010/nrs_2010_juzwik_001.pdf

Finally, a quote from a document both Dr. Appel and J. Juzwik co-authored for the Great Plains area,

“Most failures of root cutting or disruption treatments to control oak wilt are attributed to insufficient depth of treatment or poor placement of the treatment line. Several models have been developed to guide management foresters in placing the treatment line. The general approach is to place the line far enough away from the diseased trees that there is low probability of the fungus being in the roots of the symptom-free trees outside the treatment line. However, the line should be close enough that the fungus will die before reaching the treatment line. It is assumed that the fungus will die in cut or otherwise killed roots within several years; then re-grafting can occur. There is some evidence that inserts in the trench may improve their performance by acting as a barrier to re-grafting of roots, but such materials have had only limited use. Felling of all oaks within a treatment line and even extraction of the stumps has been used to increase success of treatments in some state programs.”

Roguing in the Trench

This is, unfortunately, another neglected aspect here in Texas. The purpose of roguing is to make the likelihood of re-grafting across a containment trench/barrier line almost non-existent. By its very existence, it is an inherent affirmation that re-grafting can be a serious threat of failure for the containment project. Often it is presented as a means to strengthening or improving of the trench. Instead of containment it rather favors in all practical purposes an eradication of the disease. Up north it is called: “cut to the line.” Standard approach by most Northern States is to install what they call the primary line and often even a secondary line. These barrier lines are usually trenches effected by what is called a vibratory plow. This big machine basically has a 5ft. long spade-blade that mechanically vibrates and breaks/disrupts all roots to that 5ft. depth. At a minimum, the trees in between the primary and secondary barrier lines (in some cases every tree in the disease zone) are girdled and or cut down and or herbicide is applied to them in order to avoid any chance of re-grafting and thus future trench failure.

National View/Standard Practice for the Northern States

“Root graft disruption can be made even more effective by removing all oak trees inside the barrier lines following plowing or trenching. Removing these trees and optionally treating the stumps with an herbicide helps ensure that all of the oak roots inside the barrier will die before root grafts can be re-established. This practice is sometimes referred to as cut to the line. Although this is a radical treatment, it may be useful in areas where oak wilt eradication is the goal.”

How to Identify, Prevent, and Control Oak Wilt

They are well aware that failure is a way too costly a proposition. I wish the Texas protocol, which must deal with numerous species much more prone to re-grafting and soil characteristics, which force root re-growth into a shallow, close-knit zone, would follow suit with a goal for full eradication.

Texas Practice

There is some mention of roguing options here by the Texas Forest Service. For instance: “Trees within the 100-ft. barrier, especially those without symptoms, may be uprooted or cut down to improve the barrier.” I am of the firm conviction that the use of “may” must be changed to “should.”

“Trench depth, placement, and tree removal inside trenched area are critical to success.”

Texas Oak Wilt Suppression Project

Why has a “critical” factor been laid aside?!

I regularly visit trenches that have experienced a breakout after re-grafting because this option and the strong likelihood of failure was not explained to them as a very likely probability if they failed to implement a roguing component to the trench. What actually happens is a practice that will almost guarantee a failure – namely that within TFS guidelines contractors are allowed to treat with fungicide inside the trench – which in every instance happen to mostly be every non-symptomatic tree (obviously the ones near the edge of the trench perimeter). This practice of treating with fungicide in almost every case will not only guarantee infection but survival and root regeneration and growth from both sides of the trench. Rarely, are the consequences ever communicated to the trusting client. Don’t believe me? From the TFS oak wilt website (“Quick Guide” section) – “Cut or uproot all trees within the 100-ft. barrier (except those injected with fungicide).”

In contrast, Dan Wilson states:

“Because live oaks on both sides of the trench have roots severed by trenching, these trees send out an abundance of new feeder roots into trench soil creating conditions very favorable for the formation of new root grafts across the trench. It is for this reason that the TOWSP recommends uprooting all trees and disrupting or extracting the root system inside the trench in rural areas.”

https://texasoakwilt.org/assets/professionals/NOWS/conference_assets/conferencepapers/Wilson.pdf

Here again, Wilson sets forth the facts that expose how conflictory the practice of allowing fungicide injections within the trench is with the recommendation of roguing which they state aids in strengthening the trench.

Silvicide/Herbicide

Silvicide or use of herbicide to kill trees has the following three major means of functioning as powerful weapons of war in the oak wilt battle: 1) killing and drying out infected red oaks thereby eliminating the capacity for mat formation, 2) the means of making trench efficacy permanent as well as the most valuable benefit of all – 3) stopping oak wilt permanently without any trenching.

Northern State Experts

Below I provide evidence that the most advanced research states in the north, which also happen to be the worst affected states, are commonly utilizing herbicide from their war chest of weapons against the disease. The Wisconsin and Minnesota links are by far the best exposition of what is possible and show that if we stay in the fight – we can make huge gains against this vile adversary. The adaptation of these practices will garner major gains for Texas as well as those states who may not yet be incorporating them.

National View

“Root graft disruption can be made even more effective by removing all oak trees inside the barrier lines following plowing or trenching. Removing these trees and optionally treating the stumps with an herbicide helps ensure that all of the oak roots inside the barrier will die before root grafts can be re-established. This practice is sometimes referred to as “cut to the line”.”

USDA Forest Service

Kyoko Scanlon, a Wisconsin DNR forestry researcher is conducting a 50+ oak wilt mortality center study of containing oak wilt with a silvicide-only approach. The herbicide containment of oak wilt study which was funded by the USDA Forest Service can be found in the link below.

https://silvlib.cfans.umn.edu/content/5-year-oak-wilt-containment-study-wi-dnr

Wisconsin

Tom Lovelien, a Marathon County forester has since 2003 had excellent success with a silvicide-only containment approach. It is his success which principally inspired the USDA Forest Service study by Kyoko Scanlon currently in progress (see above).

Click to View

Michigan

“An alternative, less expensive treatment that has had some success is double-girdling and applying herbicide to trees along the disease perimeter. Chainsaw girdles need to extend about two inches into the wood, then the herbicide applied into the cuts.”

https://www.canr.msu.edu/news/understanding_oak_wilt

In addition to Tom Lovelien and Kyoko Scanlon (Wisconsin), another pioneer in this new approach to containment hails from Michigan. Dr. David L. Roberts is a premier research pathologist who recently retired from the prestigious Michigan State University. He has engineered a “cupping method” of introducing the herbicide which is superior to the traditional girdle method as well as utilizing an herbicide that in my assessment will also have superior results killing the roots of Quercus rubra.

Minnesota

“Apply an herbicide to the stumps soon after cutting to reduce the time that stumps and roots stay alive and sustain the disease. Use an herbicide labeled for cut-stump treatment and carefully follow label directions.”

Pennsylvania & West Virginia

“In the Pennsylvania control program…the surrounding healthy trees are cut to prevent spread by root grafts and to prevent above-ground spread of the pathogen by eliminating the nearest suscepts. Herbicide application to the stumps hastens root kill, shortening the time that the roots can serve as reservoirs of inoculum and pathways of below-ground fungus spread.” “The Pennsylvania control method prevented nearly all spread of the oak wilt fungus to trees in the immediate vicinity of treated infection centers. It was about equally effective in all test areas from Pennsylvania to southern West Virginia.”

This is an excellent example of an older study utilizing herbicide – clearly displays that herbicide has and will continue to play a more and more effective roll in oak wilt control.

https://www.fs.fed.us/ne/newtown_square/publications/research_papers/pdfs/scanned/OCR/ne_rp204.pdf

Indiana

“However, if there are obstructions that interfere with digging or cutting (such as pipes, power lines, cables, etc.), professional applicators may use chemicals to disrupt root grafts.”

www.extension.purdue.edu/extmedia/BP/BP-28-w.pdf

Texas Experts

Except for an occasion or two – neither of which were even scientific or whole-hearted enough to warrant publishing or recording of the attempts to stop oak wilt with herbicide and no trenching by TFS personnel, herbicide use in oak wilt control here in Texas is very rare.

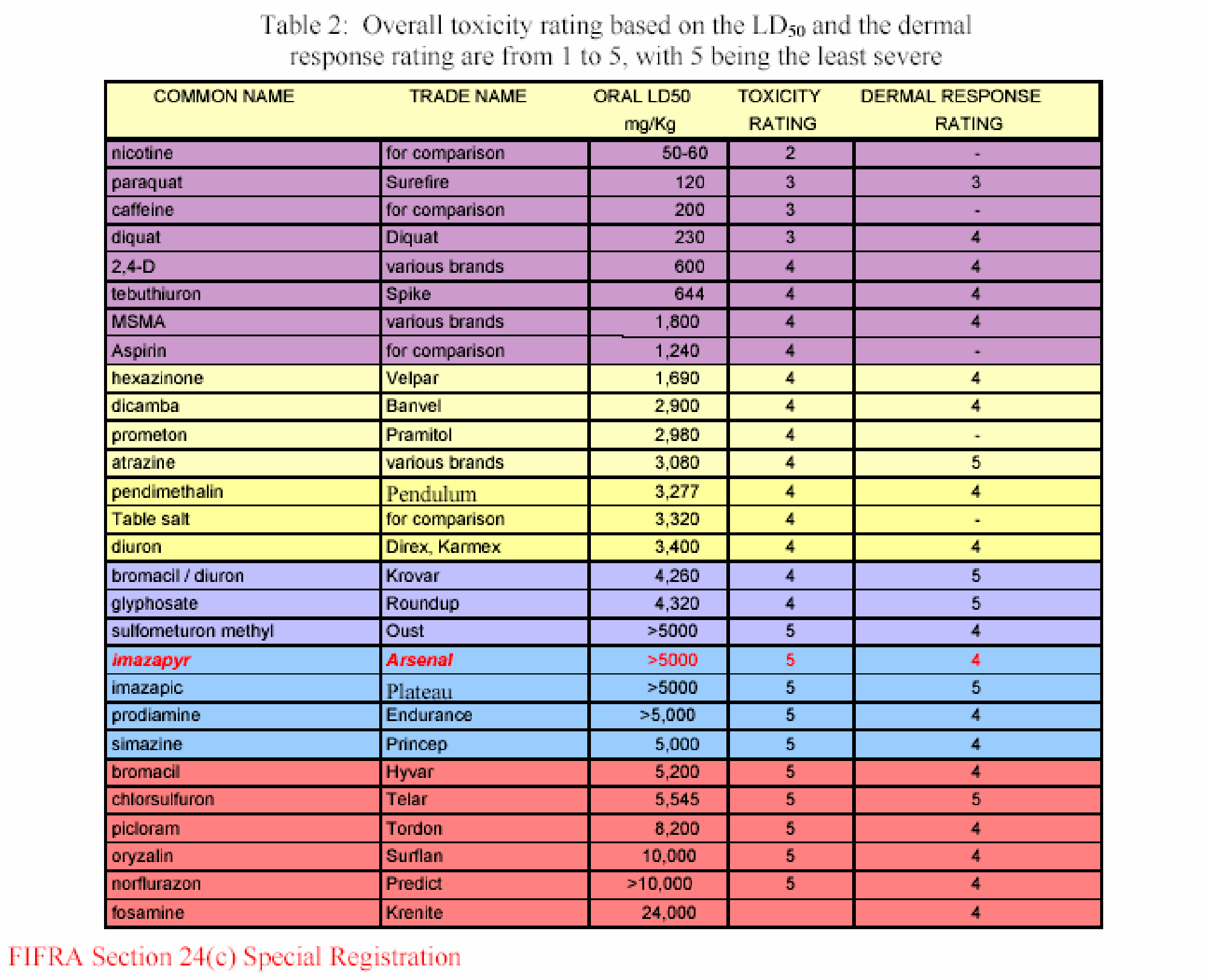

It should be noted that on texasoakwilt.tfs.tamu.edu regarding infected spore producers it is recommended “(SP) trees should be injected with herbicide…” What concerns me here with this use is the likelihood of the other options of: girdling and stripping of bark, or cutting and burning, or using a Barco type flail chipper machine are all much more difficult than herbicide control – leading me to conclude that herbicide action should be the most heavily utilized method of war on infected red oaks, but it is not. There is no typed word of this in the current Texas Oak Wilt Qualification (TOWQ) course 87-page presentation for expert arborists other than one single picture, and none found within Texas Agrilife primers, etc. The couple of silvicide attempts by the TFS to stop oak wilt expansion through Live Oaks without trenching obviously failed here in Texas. It is extremely unfortunate that so few trials were conducted while so much time, energy, and money were invested in the most expensive and unaffordable method possible - trenching in rock. Rocksaw or spray bottle? Not a hard one to decide right? The fact is that a cheaper, easier, and even more effective means of oak wilt control as a secondary effect of pasture improvement projects can work without any trench installation. It is also an unfortunate fact that when trenches are installed – it is recommended that roguing – or bulldozing trees within the trench is suggested, but a silvicide approach within containment trenches would be much less costly and damaging and at the same time more effective.

The Texas Parks and Wildlife Department in this PDF, under Appendix W, provides a strong “sales pitch” for the preferential use of Arsenal AC in their various herbicide programs.

Click to View.

SILVICIDE IS ONE OF THE PREIMMINENT GAME CHANGERS FOR TURNING THE TIDE IN THIS WAR.

Tree Planting

If there is one thing I get across here it is this – diversity is a critical component in the long-term war on oak wilt. Further, we must embrace a diversity that includes some non-native, adapted or naturalized species that are non-invasive. The hope for a host of resistant white oak species options is turning out to become a mirage that will end in even more losses to this disease in subsequent generations of those white oak that were, are, and will be planted. The one that shows any promise in that is the Post Oak – the one tree nurseries don’t have nor even want to try to grow. At any rate a percentile of oaks somewhere in the 20%-40% range would be a wise recommendation when looking into defining oaks part within the topic of diversity. A comprehensive list of trees that will grow here in Texas can be found on my Trees webpage.

The TFS shares this approach:

“Planting a variety of tree species can lessen the impact of the disease. It is best to plant trees that are native and/or adapted to your local environment. Native trees also provide habitat for local bird and wildlife species. Avoid planting a monoculture. Plant a diverse selection of tree species to defend against any future forest health issues.”

https://texasoakwilt.tfs.tamu.edu/oakwilt/oak-wilt-management

Recommended Improvements for Increased Efficacy of the TOWSP

Historical Project/Current Form Project

(1998-2007)

Most Current Form of Project (2018-to present)

Texas Oak Wilt Suppression Program Improvements

This was a San Antonio Arborist Association Education Event.

2025 Recommended Texas Oak Wilt Suppression Project(TOWSP) Protocol Adjustments

-

Establish a board consisting of TAMFS personnel, AgriLife personnel (lab director, herbicide expert, Superstar program leader), A&M researcher(s) and Texas A&M Board of Regents rep., Rainbow Ecoscience and Arborjet and Mauget reps, ISATX chp personnel, BCMA/CA reps, MA/UF reps (isa reps should be conditioned by the requirement for technical and highly experienced experts in regards to oak wilt). All technical advisory board members should be committed to progress and results. Annual board meetings along with a written list of goals and a process for evaluation of those goals and make that information available for public disclosure via Open Records Request/PIR.

-

Mandatory public constructive feedback form for all citizens who receive a TAMFS personnel visit to their property for oak wilt after one year has passed from that time and ongoing request for feedback every five years from those who receive cost-share support. An online submission form must be provided on texasoakwilt.org website for the remaining public. All constructive feedback must be made publicly accessible – avoiding the need for an open records request to be issued for those who wish to see the feedback provided regarding the TOWSP.

-

Protect use of TAMFS personnel time for more effective macro-forest health tasks by directing all single property requests by the public to contact TOWQ arborists for first visit (Ex. The 2020 policy of the City of Austin).

- Change cost share allocation to a 50/50 ratio for trenching and infected Spore Producer (SP) identification and their removal/herbicide.

- Prioritize SP-centric scouting and eradication paradigm all year long above beetle/wound-centric paradigm in public message campaign. Included with this must be a strong public message that emphasizes the frequent occurrence of natural wounding which we have little ability to effectively mitigate other than SP removal prior to mat formation.

- Especially focus on increase of herbicide option for SP destruction from Spring – Summer months.

- We paint all year because fungal mats form all year – it only takes one; update public message announcements that: THERE IS NO SAFE TIME TO PRUNE BUT PROPERLY APPLIED PAINT WORKS ALL YEAR LONG - INCLUDING SPRING.

- Public service message should explicitly state that all consumers should give due consideration to only hire contractors with an ISA certified arborist on staff to prune the same way they would choose a licensed electrician to perform dangerous and critical electrical work.

-

The entire, unedited exposition of the document titled: “Pruning Guidelines for Prevention” (www.texasoakwilt.tfs.tamu.edu; move from “Professional Literature” to “Community Tools”!) should be always and only and in its entirety recommended for community codification. Other human activities such as damaging trees with machinery, removing underbrush that is protecting trunks from deer rubs, having horses that crib on trees without protective fencing, etc. are just as important actions to take as is using pruning paint.

-

All TOWSP protocol will assume that interconnected or grafted roots are at a minimum a common occurrence and in many cases an almost guaranteed fact.

-

Non Cost Share (NCS) trenches by definition do not contain the disease, and therefore no TFS agent is allowed to spec out and recommend a NCS trench as a recommended suppression option without requesting a waiver from the TFS Forest Health director within which substantive argument is made that there is a extremely high probability that the disease will result in delaying or redirecting the disease for large oak populations for a decade or more. All NCS waivers must be made available to public access and must be included in Post Suppression Evaluations (PSE).

- Increase standard trench depth to 5’; waiver form required for 4’ if meets pre-requisites for soil, topography, and tree size/species.

- Fungicide application prohibited within 50’ of the trench without a waiver.

- Required selection of roguing option – either herbicide or uprooting all non-symptomatic trees within 50’ of trench; waiver form required and applicable if no oak species within 50’ on the healthy side of trench.

- Begin trial studies of “pasture improvement” projects over oak wilt centers when landowner prefers that particular option over trenching and as the standard approach in those occasions trenching is not feasible.

- PSE's to be conducted only of trenches at 5 and 10 years of age; trenches younger than 5 years will only be visited and documented if a Texas Oak Wilt qualified arborist assesses that a cost share trench has failed. ALL PSE must be made publicly accessible without need for recourse via Open Records Request.

- Devise a public campaign message asking for the exclusion of the term “resistant” regarding white oak species and define tolerance in terms that address consumer concerns and that field observations are concerning and research forthcoming (hopefully).

- Develop protocol for infected white oak species foliar symptoms identification and treatment techniques and incorporate into the TOWQ program.

- Encourage planting only one or two oaks per every five trees installed and that their location and spacing is intelligently selected.

- Make a prioritized list of needed research: gigh-success thereapeutic fungicde treatment protocol, alternate mode of action fungicide in order to counter fungicide resistance, provide alternative labs that perform dna testing (at least until A&M can successfully offer this superior testing method), silvicide “trench” only, silvicide and more shallow trench depths, true tolerance level of each white oak, can Bur Oaks in Texas also form fungal mats, do Post Oaks serve as conduits for inter-species root transference and if so how frequently, exhaustive root-grafting within various trench depths, widths, both intra-species and inter-species, re-visit trench insert studies and continue the studies, study fungicide soil drench alone and combined with macro-injection

- In the absence of published research – field observation, intelligent and experienced judgements and corresponding action is the modus operandi